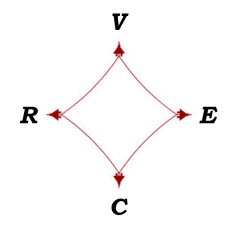

Leadership Diamond©

Vision:

Vision

[Peter Koestenbaum] To see the larger perspective.

On Leadership Vision

Pilot statements from Professional Pilot Magazine and Aviation.Org subscriber surveys.

Anticipation, Awareness, Exercising Judgment, Maintaining Options, Thinking Critically, Making Decisions

Pilot views on cockpit leadership vision are paricularly instructive. Pilots respect pilots who:

- anticipate and think ahead.

- stay “miles ahead of the aircraft.”

- maintain the “big picture.”

- exhibit “common sense” (exceptional judgment), thereby keeping out of bad situations.

- play out multiple scenarios, consider available options and select the best course of action.

- maintain situation awareness.

- are skilled at communication and, importantly, articulate their intentions.

- are optimistic and maintain a positive attitude.

- have a passion for flying and love what they do.

Cockpit Leadership Vision

Vision is thinking big, seeing and sensing the big picture. Pilots, through personal development and experience, cultivate thought processes that expand their view of flight missions being undertaken.

Professional pilots improve their intuitive judgment by anticipating and preparing for the flight phases ahead. Preparation, anticipation, and intuition are ingredients needed to gain and maintain the bigger picture.

Do we visualize the forecast weather conditions enroute? On arrival? Are they expected to be transient or stable? By comparing what we actually encounter with what we had anticipated we are better able to deal with change and, as an example, be far less likely to make impulsive approach decisions.

Are we flying into an area of higher or lower pressure? Stories are plentiful regarding improper altimeter settings at destination, and we know the outcome of such errors can be disastrous.

Is the approach lighting what we envisaged? Does the runway ahead fit our expectations? Width? Length? Tower location? Landing on a taxiway or at a wrong airport does happen and is fraught with risk. In the embarrassing category, we recall the DC-10 that landed at Brussels instead of Frankfurt. Since the cabin had a large moving-map display, passengers were aware of the error before the cockpit crew.

Do we mentally fly the approach before arrival, actively considering altitudes, configuration, step-downs, missed approach, obstacles, terrain, etc.? Might tragic CFIT accidents have been precluded had the approaches been mentally pictured and rehearsed?

These illustrations are practical examples of visualizing potential outcomes. The ability to anticipate and form mental images undoudtedly varies from pilot to pilot. Nonetheless, we as pilots should commit to improve our ability to visualize situations and, in the process, think strategically and continue to mature as cockpit leaders.

Pilot Judgment

The capacity to assess situations and draw conclusions. Judgment occurs whenever change is detected and, through the selection of a preferred alternative, determines the decision to achieve a desired outcome.

Once change is detected (awareness), the resulting judgment may be intuitive (reactive) or cognitive (thoughtful).

- Intuitive judgment predominates and is based on training, experience and established personal/professional standards.

- Cognitive judgment is the result of a deliberative process that evaluates options and potential outcomes.

Judgment is largely intuitive since pilots would otherwise be overwhelmed by events. However, on occasion, it is wise to “override” the intuitive response and act more deliberately.

Choices, Choices . . .

Preflight

Well-ordered preparation is one key to mission success. Although pilots may not think of it in these terms, all play a “What if?” game during the preflight planning and briefing stage when studying weather, winds, routes, airports, fuel requirements, etc., and when anticipating how the changes that may occur will affect the flight. Thinking “What if?” helps to prepare for the choices needed to make to meet flight objectives.

Inflight

“What if? . . . Then” in flight is one effective means of preparing for the choices pilots will need to make. “What if?” scenarios help to bring the unanticipated into the world of reality.

Pilot Judgment

Fundamentally, pilot judgment is making choices. Anticipating potentially adverse outcomes improves pilot judgment by preparing to make reasoned choices when they are necessary.

$$ in the Bank

[Airline captain] When I’m rolling out I want to have at least one option left.

Digging for Options

Pilots are mission oriented. In civilian aviation the motivation to fly is no more pronounced than when providing helicopter emergency medical service (HEMS). Lives are at stake making the drive to succeed particularly intense.

For any intended flight, the judgment to launch and assumption of the responsibility for the flight’s safety requires the evaluation of options should the flight environment change (e.g., weather conditions, mechanical or instrument anomalies). What are the alternatives when flight risks increase, and are these options adequate to ensure safe conclusion of the flight?

Most pilot experiences are far less dramatic than emergency health services, and a lower pressure to push on presents itself. Nonetheless, the same principles always apply. Evaluate options, and never get down to the last one. Always have an out. Available choices may not be readily apparent—digging for them demands keen and thoughtful analysis.

Digging Deep

Comparing and evaluating options is essential, but not enough. Choices may not be readily apparent. As CRM pioneer Capt. Bob Mudge always emphasized, “You’ve got to get at the alternatives and identify them in the first place!” Explore! What are the weaknesses in my thinking? What can go wrong?

“What if?” is a means of determining potentially adverse situations, but Bob’s point is the best options need to be uncovered.

Intuition

Considering judgment’s distinction between intuitive and reasoned methods of choosing options, it seems appropriate to consider this quote:

[Albert Einstein] Intuition does not come to the unprepared mind.

In this context, this great man is saying that good judgment is the product of conscious effort and not an innate ability.

There’s hope for us all.

Scenario building, a proven aid to the judgment process.

Asking and answering “what if . . . then” can lead to an effective Leadership Diamond© Vision strategy.

FAA Safety Tip

The FAA’s endorsement of the What If? line of questioning provides welcomed emphasis.

FAA Safety Tip (NOTC2035):

[FAA] Why play “What if?”

- It’s an excellent strategy for runway safety and risk management,

- Prepares pilot’s for making choices when needed,

- Promotes sound judgment – you plan those choices when you are not under pressure,

- Covers many bases, not just one option,

- Improves situational awareness,

- Heightens pilot awareness.

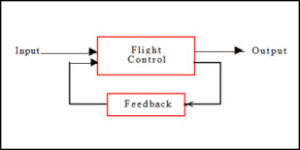

Decision making is a control process characterized by the feedback loop: Setting an objective; Seeking feedback; Taking corrective action; Committing to success.

On Making Better Decisions

Decision Making, A Thinking Process

A Slide Presentation in the Cockpit Leadership Library

* Courtesy of Dan Gurney *

[Dan Gurney] Making decisions is a process that involves:

- understanding the situation, the problem, time available, workload and risk

- the control of our thinking, attention resource and mental behavior

- experience and knowledge to generate options

- risk assessment and judgment

- choosing a safe option

- taking action

- checking.

What’s Next?

Asking, “How many altitude busts, missed step-downs, improper procedure turns might have been avoided if the question “What’s Next?” were routinely answered?”

Defining the Tasks Ahead

The mark of a cockpit leader is good judgment. Confident and consistently sound choices gain recognition and peer respect. “What if?” scenarios can be helpful in elevating the quality of a pilot’s judgment.

The mark of a cockpit manager is execution. The choices made need to be transformed into action, the “decision making” process. Concepts must be defined in explicit terms for the resulting actions to be meaningful and effective. That is, very clear goals need to be defined with acceptable boundaries. Progress towards the defined objective needs to be monitored and corrective action taken, as necessary.

This process, too, can be aided by examining what needs to be done to achieve the intended result. By asking “What’s next?” pilots keep defining and redefining the tasks ahead that are necessary to accomplish their objective. All too often targeted goals are poorly defined or progress tracking is lost—decision making is not in control.

Considering all the variables of flight, there are multiple interrelated decisions in play at any one time. It can be difficult to sort out the tasks and maintain the necessary mental discipline. Structured thought processes can be beneficial, particularly when the workload is high, and, just as thinking “What if?” can benefit pilot judgment, thinking “What’s next?” can benefit pilot decision making.

How Low?; How Far?; What’s Next?

In Reality’s paragraph on Stabilized Approach, one pilot commented:

[General aviation pilot] I think about each segment of the approach using three questions: (i) “how low?”; (ii) “how far?”; (iii) “what’s next?”.

All pilots will benefit by this extended critical thinking.

Awareness

The Vision : Reality Connection

Seeing the situations that exist and anticipating the near future.

A pilot maintains situation awareness when active choices are made, goals are targeted and progress towards these goals is tracked.

[Wayne Gretsky] It’s not as important to know where the puck is now as to know where it will he.

On Situation Awareness

Vision—Summary; Projecting Flight Conditions

Gaining and Maintaining Situation Awareness, a Slide Presentation in the Cockpit Leadership Library

(Excerpts)

* Courtesy of Dan Gurney *

Thinking Ahead—Projection

An accurate understanding of the situation is essential for planning ahead,

You will be able to:

- Judge when will something could happen – time, place, or event

- ‘Make’ time for seeking options, choosing, and deciding

- Consider future hazards and make risk assessments

- Forecast the flight path, detect trends or errors

- Set objectives for the next phase of flight

- Plan and share workload

- Readjust the plan

- Think

Thinking ahead prepares for decision making.

Thinking Ahead—In Practice

Thoughts and considerations:

- Set time or place markers for rechecking the situation

- Confirm that the future situation agrees with the plan

- Set priorities regarding the current situation

- Rules

- SOPs

- Set priorities for thinking

- Workload

- Attention

- Task

Failing to Think Ahead

Failures in thinking:

- Not planning ahead (“What if?”)

- Invulnerability—it could happen to you

- Poor judgment—follow SOPs

- Alternatives not considered

- Failing to monitor and review

- Continuing with the wrong action

- Poor prediction of consequences

- Reluctant to change plan

Reality-Based Vision

Concept Alignment

The developer of the Quantum cockpit management system, Bob Mudge, believes it is important to have a vision of whole flight and each flight segment, but emphasizes the pilot’s concept must be reality-based.

[Bob Mudge] If good judgment and decisions are to be expected, the concept has to be as close to reality as possible. That is, the pilot’s vision needs sharpening to fit new information as the flight progresses.

Concept Alignment Process

This process is an ongoing, structured communication pattern that addresses any situation that may be anticipated that Bob describes as follows:

[Bob Mudge] The PIC or PF is required to make a statement of concept, one pilot communicating to the other crew member how he or she visualizes a situation. For example, “We’ll fly at flight level 310 at Mach point eight-one with eight-two and eight-zero as our tolerances,” thereby giving the monitoring pilot the tools needed to monitor this situation. The other pilot must then affirm or challenge the statement.

But, as Bob points out, both pilots can still be wrong.

Challenging

[Bob Mudge] For this reason, both pilots throw stones at the statement of concept. Where can it fail, where can we go wrong? Is there a problem we haven’t foreseen? Then, if a weakness is found, how do we handle it? If the SIC or PNF disagrees with the statement of concept then that pilot challenges it—“I see it this way,” for example.

During this process either pilot may routinely challenge the other’s concept of the situation. Bob continues:

[Bob Mudge] The challenge is solicited. It’s welcomed. It’s expected. Required by this concept alignment process, the situation challenge does not challenge authority, but is used to achieve common understanding.

Verifying

[Bob Mudge] In addition, every challenge must be either verified or denied from a third source—the flight manual, for example. If time does not permit or the safety of flight is in jeopardy, then the most conservative response, either challenge or statement, must be taken. If time permits, then verify or deny. This procedure allows the crewmembers to move their concept as close to reality as they can for all phases of the flight.

The Single Pilot

[Bob Mudge] Concept alignment not only refers to conceptual harmony between two crew members, but also to the process of aligning every concept with reality. It’s a structured thought process—challenge and verify—that is valid for the single pilot to utilize as well.

All-Encompassing Vision

When discussing pilot vision, Jack Enders, former president of Flight Safety Foundation, thinks of grasping the whole mission and characterizing what lies ahead, “a situational awareness perspective of what the pilot’s faced with.”

[Jack Enders] My ability to picture what lay ahead depended on the stage of my piloting career. In fact, sometimes I dream I’d like to go back to flying knowing what I know now.

In the Air Force’s Strategic Air Command we were tasked with accomplishing missions, were thoroughly briefed, and in that sense had some expectation of what we’d run into.

When flying specific test missions with NASA my attention on what lay ahead was sharpened. I had to develop a sense of the outcome and how to achieve it. That is, if one strategy didn’t work, then what would I do instead.

To Mike Malherbe, international airline training captain, vision is “the ability to ‘see ahead,’ the development of a dynamic model of the aircraft and flight progress that spans the pilot community.”

[Mike Malherbe] I believe pilots develop an all-encompassing “vision” called situational awareness—in simple terms a capability of monitoring the progress of the flight—a type of “howgozit” if you like. Situational awareness is a vital element of any flight and is relevant to all facets of aviation, from small aircraft to jumbo jets.

Looking Ahead

Norm Komich recalls three situations that span his career and illustrate the need for forward vision.

[Norm Komich] In pilot training, as soon as the weather briefing was completed, some people were already thinking about what the destination active runway would be.

Conversely, I learned about an airline flight when, at altitude near the end of the flight, the captain asked the first officer for the altimeter setting. Well, it was 3052 but the FO said “2952”—they were 1,000 feet off! It happens, but how can an experienced crew be so unaware of the low versus high pressure system they were flying in? Yet they were oblivious to it, and just took the number and stuck it in.

Going through my IOE, my instructor made similar points about thinking ahead. He said, for example: “As soon as you read the tail number on the dispatch papers you should be thinking of the idiosyncrasies of that airplane. Where’s the flight director located? The GPWS?”

General Aviation

Norm relates his thoughts on looking ahead to general aviation training.

[Norm Komich] The new general aviation pilot would benefit if the desirability of thinking ahead were really pointed out and not just part of a quick discussion. If every time he flies he were to instinctively ask himself, “What will the active runway be?,” or “Will I be i n a higher or lower pressure situation?,” or similar questions, then he would b e that much better prepared. This approach could be built into everyone’s flight preparation.

Procedures Role

While Norm agrees that the ability to visualize what lies ahead is a valuable asset, it is at times insufficient and a practiced procedure may be necessary. He provides an example.

[Norm Komich] In pilot training I practiced entering holding patterns. There are a thousand ways to enter! I looked at the RMDI and the outbound course passing over the holding fix and, knowing the direction of holding, could figure which way to tur n for a direct, parallel or teardrop entry. It was really very mechanical. and I did it the same way in the airline industry.

Entering holding back then in training, I screwed up. I didn’t have the procedure fine-tuned. Well, the instructor pilot up front said, “Wow, that was really good. I guess you heard me talk about that thunderstorm and you maneuvered to go around it.” Actually, I didn’t have a clue what was going on!

Apparently some pilots can picture in their minds the racetrack patterns and can figure out the holding entry. Even though I’ve tried, I can’t do that. All it does is confuse me. That’s why I use this mechanical method that doesn’t leave as much opportunity for me to screw up.

Most pilots can relate to Norm’s difficulty since the pattern itself is a track in the sky with no visible reference points. A consistent and reliable procedure helps to avoid confusion, particularly when the workload is high.

Broadening Vision’s Scope

Leadership vision takes full advantage of the pilot’s imagination and employs all the senses. “Gut feeling,” intuition and instinct may be felt rather than seen, but play heavily into the pilots concept of the here and now.

Like Jack Enders, Rick Heybroek, founder of Royal Aeronautical Society’s Human Factors Group, believes:

“Pilots develop a deeper sense of vision over time, an intuitive sense of the rightness or wrongness of a situation.”

Rick cites CFIT accidents as examples of when “vision cuts in too late,” and the Dan-Air accident at Tenerife is particularly illustrative.

[Rick Heybroek] Due to conflicting traffic a charter from London was placed in an unpublished hold by Tenerife ATC. The crew misheard the hold clearance as “turn to the left” while the ATCO thought he had said “turns to the left.” Dan-Air came onto the new heading, and the captain belatedly remembered his Minimum Safe Altitude after commenting that “something wasn’t right.”

It bears repeating, confident pilots learn to trust their gut instincts and are prepared to act upon them.

Passion

Passion, this love of flying. feeds all our senses. Quoting other pilots, passion is “a sense of discovery that is aviation,” an intensity that “touches every aspect of our beings, sharpens our understanding of situations, helps us to anticipate events and provides clarity to our thinking.”

[Amelia Earhart] I have often said that the lure of flying is the lure of beauty. That the reasons flyers fly, whether they know it or not, is the aesthetic appeal of flying.

[Charles Lindbergh] Science, freedom, beauty, adventure: what more could you ask of life?

Being Prepared

[Norm Komich] Here are practical cexamples of flight preparation:

The Captain who kept a list of his memory items on the back of his visor in his car so that every time he drove to work, he could review them.

The military toilet with the memory items on the back of the door so that every “constitutional” provided an opportunity to review them.

On Critical Thinking

An Introduction to Situation Awareness and Decision Making

A Slide Presentation in the Cockpit Leadership Library

* Courtesy of Dan Gurney *

[Dan Gurney] Critical Thinking provides the mental control and discipline required for situation assessment and decision making.

A few thoughts to consider:

Self Questioning:

- Am I biased in my thinking?

- Have I made a plan for what I want to do?

- Are my ideas or knowledge on this issue correct?

- Am I aware of my thinking; what am I trying to do?

- Am I using all of the resources for what I want to do?

- Am I evaluating my thinking, what I would do differently next time?

- Am I aware of how well I am doing; do I need to change my actions or intentions?

Planning

The process of about thinking what you will do in the event of something happening or not happening.

Expert Thinkers

- Focus on relevant issues

- Identify essential information

- Consider information on merit

- Test and check the basis of their awareness and decisions

Personal Briefing

Before flight, self briefing reinforces memory cues and knowledge—these aid the recall of information for the use in situation assessment and decision making.

- Know on what, who, where, and when to prioritize you attention

- Always brief routine operations – repetition aids memory

- Structure the briefing along the intended flight path

- Visualize your actions (plane, path, people)

- Consider the significant threats

- Recall lessons from training

- Refresh SOPs

- Questions

The Critical Thinking presentation in the Library provides an expanded view of critical thinking in aviation settings.

[Dan Gurney] Critical thinking is at the center of all safety processes and human activity

Planning

[David St. George] Quoting General Dwight Eisenhower, “Plans are nothing, planning is everything.”

[David St. George] Every plan undertaken in aviation must contain the firmly held understanding that it is only a hypothesis, an enterprise subject to change from its inception until the chocks are in place.

Pilots must embrace change and flexibility to be able to respond to dynamic conditions.

“Does this make sense in relation to my overall standards and objectives?”

[Mike Tyson] Everybody’s got plans until they get hit.

Defining the Vision of the Flight

The Preflight Briefing

Briefing Guide. The Operator’s Guide to Human Factors in Aviation (OGHFA), a project of the Flight Safety Foundation (FSF) European Advisory Committee.

[OGHFA] Briefings are an essential part of flight preparation and represent a critical moment for team building, leadership establishment and an opportunity to gather and select all operational data pertinent to the upcoming flight.

The following points apply to all flight briefings:

- Briefings should be adapted to the specific conditions of the flight and focus on the items that are relevant for the particular takeoff, departure, cruise or approach and landing.

- Briefings should be interactive and allow for dialogue between the PF, PNF and other crewmembers.

- Briefings should be conducted during low-workload periods.

- Briefings should be conducted even if the crew has completed the same flight many times in the past; vary the briefing approach or emphasis when on familiar routes to promote thinking and to avoid doing things by habit.

- Briefings should cover procedures for unexpected events.

- Pilots should not fixate on one particular aspect of information in a briefing, as other important information may be missed.

Flight Briefings

[Norm Komich] Everyone wants a good briefing. The briefing sets the tone of the flight. No matter how often you fly with the same crew, give a thorough briefing. A good briefing is not a regurgitated laundry list—a good briefing covers specific issues of THAT flight.

[Norm Komich] Familiarize yourself with the unfamiliar. One of the best suggestions of a briefing I ever heard was to cover some random abnormality at every briefing—familiarity facilitates accomplishment.

On Making Better Decisions

Preflight Briefing

A Slide Presentation in the Cockpit Leadership Library

* Courtesy of Dan Gurney *

[Dan Gurney] We learn from briefings, they are “the flight plan for the mind.”

Planning and thinking ahead by visualising, enables:

- Preparation for events so that they can be done more efficiently

- Anticipation of high workload situations; task and time reallocation

- A reduction of unanticipated or ‘surprising’ events which minimizes stress

- A cross check of progress against the plan and an earlier recognition of situations

Flight Preparation

Prelight Briefing

Blue Angels Briefing and Debriefing, a Video Presentation in the Cockpit Leadership Library

Flight Preparation

Nothing is taken for granted.

Before every flight, reviews are conducted regarding:

- Normal and emergency procedures

- Aircraft limitations

The Blues flight preparation is thorough as they go through each maneuver

- Each pilot concentrates on the mission to be flown

- All have the opportunity to raise issues/concerns

Mental Preparation

The pilots form mental pictures of each maneuver

- They visualize what they expect to see

- Pilot: “I fly the airshow in my mind”

Mental exercise and preparation are key to improving situational awareness in flight

- Events are anticipated

- Variations that occur are understood with greater clarity

- Expectations are raised to new levels

Norm Komich’s stories on flight preparation and self-learning speak to all pilots.

[Tony Kern] Airmanship is the consistent use of good judgment and well-developed skills to accomplish flight objectives.

Airmanship

FAA 8083-3A:

- A sound acquaintance with the principles of flight.

- The ability to operate an airplane with competence and precision both on the ground and in the air.

- The exercise of sound judgment that results in optimal operational safety and efficiency.

Airmanship

Management and leadership skills are required in all aviation sectors, and certainly can be developed within the general aviation community. Bob Mudge, developer of the Quantum cockpit management system, states:

[Bob Mudge] You’re teaching a thinking process—a systematic, logical thinking process designed to control risks and lead to better judgment and decision making. Ideally this would be part of the debriefing from every instructional flight and incorporated into the tkought process of every pilot as early as possible.

Pilot Attitudes and Mindsets

United Airlines’ Skyliner Survey

Pilot responses related to Vision:

- Plan ahead for normal events and be prepared for unexpected contingencies.

- Keep your options open—never become committed to a single course of action with a high degree of risk.

- Flying must be the focus of your interest; you must want to do a good job. Stick to Standard Operating Procedures unless they are obviously inadequate.

- Eliminate distractions and maintain an alert, vigilant mental state.

- The common thread among all survivors is common sense.

- The things that get pilots in trouble are incorrect premises and fixation.

Spatial Disorientation

Visual Illusions

[Dan Gurney] Visual illusions may occur when visual cues are reduced by clouds, night, and/or other obscurities to vision. When there is no horizon, visual cues arising can easily be misinterpreted and lead to disorientation.

From the comic movie, Airplane:

Passenger Ted Striker (actor Robert Hays), a former Navy pilot, is required to take the controls because the aircraft’s pilots are incapacitated. Striker is not qualified and is completely unprepared for to fly an aircraft of this type, especially during stormy conditions at night.

Vision

In various scenes, reluctant pilot Striker’s expressions suggest his vision of the flight is clouded by stress and uncertainty as he grapples with turbulent and changing circumstances.