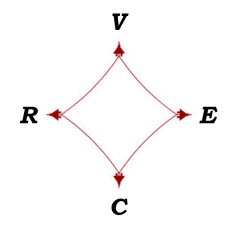

Leadership Diamond©

Ethics:

Ethics

[Peter Koestenbaum] To be of service; to serve based on principled values.

On Leadership Ethics

Pilot statements from Professional Pilot Magazine and Aviation.Org subscriber surveys.

Character, Integrity, Decency, Teamwork, Principles, Moral Force

Pilot views on cockpit leadership are paricularly instructive. Pilots respect pilots who:

- have integrity and do what they say they will do

- are honest

- are professionals and pursue the highest standards

- possess strong people skills

- create a pleasant cockpit atmosphere

- are personable, diplomatic and have an approachable nature

- treat others as they would be treated

- respect other pilots, ATC and service personnel and don’t talk negatively about others

- are team players and foster teamwork

- desire to give back “what was received starting out”

- pass along knowledge and techniques in a “non-condescending manner”

- share experiences and strive to “hangar talk”

- provide good customer service and promote good customer relations.

The pilot commits to making decisions “based on exacting standards and within established boundaries.”

On Leadership Ethics

Statements from an address before the United States Naval Academy by the then Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates.

Integrity

[Robert Gates] An essential quality of leadership is integrity. Without this, real leadership is not possible. Nowadays, it seems like integrity—or honor or character—is kind of quaint, a curious, old-fashioned notion. We read of too many successful and intelligent people in and out of government who succumb to the easy wrong rather than the hard right—whether from inattention or a sense of entitlement, the notion that rules are not for them. But for a real leader, personal virtues—self-reliance, self-control, honor, truthfulness, morality—are absolute. These are the building blocks of character, of integrity—and only on that foundation can real leadership be built.

Decency

[Robert Gates] A quality of real leadership is simply common decency: treating those around you—and, above all, your subordinates—with fairness and respect. An acid test of leadership is how you treat those you outrank, or as President Truman once said, “how you treat those who can’t talk back.”

Cockpit Communications

Maintaining a Common Understanding

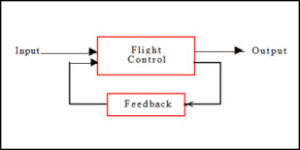

Closed Loop Communication

Crew coordination requires timely and dependable communication between crewmembers. SOPs serve as unspoken communications that cover a broad spectrum of chock-to-chock flight activities. During pre-flight briefings there is an opportunity to clarify communication requirements that are flight specific. And, during flight, two-way exchanges serve to maintain a common understanding of progress and developing circumstances. In all cases, crewmember communications need to be closed-loop. That is, there needs to be resolution of any issue raised.

Communicating Effectively

Pilots Speak Out on Communication Skills

“Sharing thoughts” coupled with being “able and ready to listen,” and creating a “speak-and-listen environment” are a few of the words that describe this ability to communicate effectively. By necessity, good communicators possess other strengths. The attributes linked to skilled communications include: having “strong systems and procedures knowledge”; sustaining “exacting personal standards”; being “humble but confident”; and possessing “good people skills.” In other words, the best know “what” to communicate as well as “how” to communicate. Importantly, they have a “conscious commitment to safety” and can accept “critical feedback.”

Decision Boundaries

Often referred to as “bottom lines” or “tolerances,” boundaries need to be established before flight and adhered to during flight and on approach to ensure control of the flight is maintained.

Controlled Approaches

Airmanship and Established Boundaries

Take Heed

[Shell Aviation] The high number of unstable approaches is disturbing.

Unstable approaches are ones that deviated from reasonable norms of near-ground approach speed, decent angle, or runway alignment.

Dramatic, Publically Reported Examples

The year 2013 witnessed two notable accidents that resulted from unstable approaches, Flight 214 at San Francisco CA (SFO) and Flight 345 at Flushing NY (LGA). Both accidents resulted from serious lapses in flight crew airmanship and disregard of piloting standards and non-observance of meaningful thresholds.

Flight 214, Boeing 777-200ER

Flight Summary

International Flight 214 was vectored to a straight-in visual approach to runway 28L at SFO. It was daylight with visibility over 10 miles and 6-7 knots surface winds. The first officer was the pilot flying. Intercepting the final approach course slightly high at 14 nm, the descent was poorly executed and the flight was well above the desired 3 degree glideslope at 5 nm from the airport.

In an effort to increase the rate of descent at this 5 nm point, the autopilot selection was mismanaged with the autothrottle being inadvertently and unknowingly deactivated. The throttles were manually reduced to idle.

At 500 feet above airport elevation the rate of descent was excessive with idle thrust! The approach continued.

The flight descended below glidepath with rapidly decreasing airspeed; however, the airspeed was not being monitored. At 200 feet the flight crew became aware of the low airspeed but delayed initiating a go-around until it was too late. The main landing gear and aft fuselage struck the seawall, the broken aircraft slid down the runway and fire ensued.

Three passengers received fatal injuries; miraculously, 99% of those aboard (including all crew members) survived.

Airmanship

A smooth entry to an approach lessens the need for deviation corrections; transition from a stable point of entry is always desirable. Flight 214 FO (pilot flying) intercepted the approach slightly high and was never fully in control of the descent.

At 5 nm from the airport and well above the glidepath, the FO changed the autopilot mode, a move that that further disrupted the descent. There is no indication that this configuration change was agreed to by both pilots.

Concurrent with the mode change, the FO reduced the throttles to idle but later failed to adequately monitor airspeed.

In this new autopilot mode the autothrottle became deactivated; therefore, later necessary thrust increases would not be automatic. However neither pilot was aware of this feature or the deactivation.

The descent continued and, upon passing 500 feet (above runway elevation), the flight was still above flightpath, now slightly high but descending at a rapid rate with the throttles full back. Large, low altitude corrections would be necessary to salvage the approach.

The approach was clearly unstable with an immediate go-around mandated.

Instead, the flight continued, descending though glide path with rapidly decreasing airspeed.

Boundaries, or Bottom Lines

The company’s SOPs required the approach to be stabilized at 500 feet above airport elevation. With the descent rate considerably above the desired glidepath rate and with the thrust levers at idle, the company’s criteria for unstable approach were met. (In fact, the approach became increasingly unstable during further descent.)

The flight crew did not consistently adhere to the company’s SOPs involving the selection and callouts pertaining to the autoflight system’s mode control panel.

Footnotes:

Systems training and visual approach training were inadequate.

More hand flying should be encouraged.

Flight 345, Boeing 737-700

Flight Summary

Domestic Flight 345 commenced a daylight visual landing approach to runway 4 at GLA with the first officer at the controls. Visibility was 7 miles and surface winds were 8 knots. There was thunderstorm activity in the area and the flight experienced tailwinds and some rain during the approach.

The autopilot was coupled to the ILS with the autothrottle engaged. Descending through 500 feet the captain lowered the flaps from 30 to 40 degrees, the prebriefed landing flap configuration and stated, “OK, we’re 40.”

A few seconds later at about 385 feet the first officer disconnected the autopilot in order to prepare for a crosswind landing.

The rate of descent lessened and the flight became above the glide slope. Crossing the runway overrun area, the pilot flying realized corrections would be necessary to be able to land in the touchdown zone. After the 100 feet callout the captain repeatedly commanded, “Get it down.” Three secords later the captain stated “I got it” and took control of the aircraft.

The throttles were advanced one second before tocchdown at a high rate of descent and in a nose down. attitude. A hard landing, the nose gear contacted the runway first. The airplane came to a stop on the runway.

The structural damage was substantial. There were no personnel injures.

Airmanship

The NTSB accident report stated the captain’s failure to comply with SOPs contributed to the accident, including nonstandard communications.

The flight crew had briefed to set the flaps at 40 degrees for the approach; however they were set at 30. During letdown the pilot not flying, the captain, lowered the flaps to 40 degrees and then announced the change. Company SOP requires landing figuration be established by 1000 feet. In addition, cockpit discipline suggests configuration changes should be made or requested by the pilot flying.

With the FO manually controlling the airplane, the flight was above glidepath as it neared the runway overrun area. The captain called to “Get it down,” and soon after—at 27 feet above the runway in a nose down attitude—took control of the aircraft (“I got it”) in an attempt to salvage the approach.

Boundaries, or Bottom Lines

The approach was unstable when descending below 100 feet in a nose down attitude, several seconds and before the transfer of control. It is apparent that no go-around/missed approach criteria had been established and that abandoning the approach was not a consideration.

Controlled Approaches

Including Corporate and Other General Aviation

Taking Heed

Accident and incident reports covering the entire aviation spectrum tell similar stories regarding the risks of unstabilized approaches to landings. ASRS reports provide descriptions of close calls in the reporting pilot’s own words that are especially instructive.

Integrity

Leadership qualities are required in all positions of responsibility. Rick Heybroek, Royal Aeronautical Society and line-oriented flight training (LOFT) simulation training developer,considers integrity as a leadership essential:

[Rick Heybroek] In my opinion, leadership is based on integrity, the uncompromising dedication to fundamental principles. Like gravity, it exists whether there are others affected by it or not.

Whether others are affected or not. Whether you are alone in the cockpit or not. Personal character is an ever-present driving force.

Rick cites civil rights activist Rosa Parks as one person who demonstrated integrity-based individual leadership. Acting alone and with deeply held convictions, she became a catalyst for fundamental change in American society.

Character

Pilot-leaders value and protect their reputations by developing and committing to a code of personal and professional standards. They share their aviation knowledge freely and have a highly developed sense of duty to their colleagues, industry and the public they serve.

Peer Influence

Being Involved

Interaction with other pilots is essential in developing and maintaining a personal code of conduct. Flight Safety Foundation’s ICARUS Committee, co-chaired by Jack Enders, observes:

[Jack Enders] The aviation operation is influenced heavily by peer behavior. . . Peer influence is a powerful tool, and should be encouraged to support professional behavior and sound decision making.

Taking the Initiative

Mentoring and more casual peer interaction are more difficult to experience in the less structured general aviation environment. It’s largely up to the individual pilot to seek out others who have related interests. Self-initiative will be rewarded.

Aviation Citizenship

When starting to fly the pilot’s focus is on personal objectives—achieving milestones and obtaining ratings. Along the way a greater appreciation of aviation’s challenges intensifies and the personal commitment to perform as Pilot-in-Command comes into sharper focus.

As Pilots:

- We are granted and willingly accept the authority of command and its attendant obligations. The underlying thought, “I am accountable,” is always with us.

- We prepare ourselves for the realities of flight and continue to learn through our own experiences and our interactions with others.

- We value and protect our integrity and accept responsibility for our actions.

- We are confident and have the courage to do what we know is right.

As Aviation Citizens:

- We are grateful for the personal freedom and privilege that aviation provides.

- We embrace guiding principles. of aviation citizenship.

[Bruce Mayes] Guard your privileges through your own behavior, and never let company or peer pressure force you into acting in a way contrary to those principles. Guard them as if your future depends on it, because your flying future—and maybe your life—does.

Pilot Attitudes and Mindsets

United Airlines’ Skyliner Survey

Pilot responses related to Ethics:

- Develop an assertive attitude and openly communicate concerns to other crewmembers.

- Keep your options open—never become committed to a single course of action with a high degree of risk.

- Even though pilots sometimes like to give the opposite impression, a true professional is responsible, diligent and studious.

- Never go on a flight with a head full of problems; leave them on the ground or stay on the ground yourself.

- Be open minded to constructive criticism.

- Always fly in the same standard way regardless of whether it is a normal line flight, an enroute check, or a proficiency check.

- Never assume anything, but verify and cross-check all critical information.

Abusing Command Authority

KLM 4805 and Clipper 1736, Runway Collision

The World’s Worst Aviation Disaster, a Video Presentation in the Cockpit Leadership Library

* Courtesy of The Learning Channel *

“A Difficult Man to Contradict”

The runway was enshrouded by fog. Clipper 747 was back-taxiing while KLM 4805 was taking position in preparation for takeoff.

The KLM captain started TO roll without either Air Traffic Control departure clearance or takeoff clearance. The KLM FO stated forcefully, “Wait, we don’t have our clearance,” The captain replied “I know that,” retarded the throttles and asked for the clearance.

Accident investigator Paul Roitsch, a senior Pan Am captain, described the following sequence of events:

- While the FO finished reading back the ATC clearance the KLM captain said “We go”, advanced the throttles and commenced takeoff roll.

- Both the FO and FE were concerned;

the FO announced that the flight was taking off;

the FE questioned the captain and FO, “Is he not clear then?” (based on the Clipper’s promise to report clear of the runway).

[Paul Roitsch] He (the FO) felt he had done his part by letting people know they were taking off. . . The Pan Am aircaft desperately tried to get off the runway. The rest is history.

[Paul Roitsch] He (KLM captain) was a difficult man to contradict, especially for a pilot such as the junior First Officer on his flight. He (the FO) did have the courage to stop him once when the captain first put the throttles up, but I don’t think he felt he could get away with it again.

The Captain

History Lesson?

Do I make myself clear?

[Captain Phillip H.S. Smith] The cry that aircraft commanders have had their authority taken away from them is not a new one. . . Legally it is quite clear that this is wrong.

The author asks why the contrary perception is so widespread, suggesting possible answers. He concludes:

[Captain Phillip H.S. Smith] The authority of an aircraft commander has not been taken away but it may be given away. . . If commanders believe that their authority is reduced they will be more reluctant to exercise that authority. This is dangerous. . . Commanders must take command.

Captain’s Authority

The possibility exists that a flight captain may tend to use the PIC authority as an excuse to act without regard to input from other crew members . On this potential abuse of trust, Mike Malherbe observes:

[Mike Malherbe] It has been my experience with some captains that they believe it is easier to make unilateral decisions rather than spend time and energy obtaining consensus. However, practical problem solving techniques and similar LOFT training normally indicate how valuable the other crew members are, and how a good manager and leader would utilize all the resources available to him or her.

Based on Mike’s experience, unilateral behavior may be less prevalent today because of modern training methods and their maturing influence.

Subordinate Roles

Acknowledging that final authority is granted to the PIC, it’s interesting to consider the role of the second in command. Bob Mudge compares the SIC’s operational and management roles:

[Bob Mudge] Operationally, if the Captain forgets the gear, the copilot says, “Do you want the gear down now?” They’ve had this shared responsibility in operations for years. No one is suggesting that if the Captain is the final authority he’s not to get monitoring and support from his crew. Sure, the PIC is in command but when he starts to fail operationally you don’t let him fail. You can’t in management either. One crucial SIC job is to monitor and support the management function.

Working as a Team

Defining Roles . . .

. . . and Avoiding Confusion

Role awareness; critical functions; crew discipline.

To illustrate the importance of having defined roles. Doug Harrington describes carrier flight deck and flight crew work ethic during aircraft launch from an aircraft carrier.

Doug Harrington states that we have lost some understanding of the roles and accountabilities of crew position and have become too focused on behaviors and the “correct ways of doing things.” Doug encourages flight crews to clearly define the roles of each crew member.

Teamwork and CRM

Fighting CRM (Crew Resource Management)

Accident and incident reports highlight the negative ramifications of poor teamwork and the adverse consequences that result from fighting CRM, imposing authoritarian rule.

Productive cockpit management requires the team members to agree on goals and immediate objectives. Without agreement, resources are wasted and personal stress levels increased as energy is diverted from flight related issues.

CRM Acceptance

Mike Malherbe, South African Airways A300 Training Captain, acknowledges existence of this point o f view exists, but finds CRM team management is accepted by most pilots:

[Mike Malherbe] I don’t believe there is a general feeling that teamwork erodes the authority of the captain. In the past, many accidents have been prevented by the assertiveness of other crew members, and others occurring due to lack of assertiveness. This has penetrated down to the ranks, and I have found a general acceptance of the principles.

However, the few “diehards” have rebelled, refusing to part with their authoritarianism, citing the erosion of authority as cause.

Making CRM Effective

CRM training developer, Bob Mudge, has a philosophic insight to this topic of authority erosion:

[Bob Mudge] Actually, the captain gains responsibility with an effective CRM program. He has to make sure this backup function of monitoring and support is in place on every flight. That’s his job.

In Bob’s eyes, if CRM training is effective, then the possible erosion of PIC authority would not be an issue.

Clarifying CRM

However, it would appear that not all such programs are fully effective. Norm Komich, airline captain and CRM instructor, comments on his experiences regarding PIC authority:

[Norm Komich] There’s some confusion on this issue. Procedures and training need to be clear and consistent.

Here’s an example close to home. A captain made the decision to takeoff when he shouldn’t have due to severe weather. Result? The FAA pulled the certificate of both the FO and SO for six months, “based on CRM.”

CRM Basics

The FAA provides this CRM Safety Tip:

- Agree on near-term objectives.

- Consider available options.

- Assign task responsibilities.

- Monitor and evaluate progress.

The Team Approach

The chain of command structure in the cockpit is vertical (hierarchical) by design, and the team concept needs to be designed around the desirable authority/responsibility relationship. Fundamentally, a team has more knowledge and skill than an individual. A team, therefore, has the potential to perform with greater effectiveness than either individual functioning alone. The cockpit leadership/management challenge is to tap this full potential.

The Cockpit Team

An Airmanship Illustration

Formal incident reports usually cite human errors that lead to undesirable outcomes. High quality cockpit performance is seldom reported and rarely acknowledged. This pop-up report is an exception.

Reality : Ethics Polarity

We learn from others, we learn from our own experiences, and we learn from thoughtful study. Ours is a complex business and we must continually learn anew.

Knowledge is the essence of reality. Sharing that knowledge not only fulfills an ethical duty, it is personally profitable; to teach is to learn again.

Sharing Knowledge

Improve and Share

[Nat Iyengar] What is required of you as an aviation professional is that you improve yourself every day, strive to be a better aviator, and everything that you learn, share it openly with the other aviation professionals in the business aviation community. Improve and share!

[Nat Iyengar] Don’t worry about proving yourself, just improve yourself!

Seeking Knowledge

Benefiting from the Experience of Others

As a second lieutenant in the Air Force, Norm Komich received six months of training before going to Viet Nam. Norm learned the frightening statistic that 80% of the pilot losses occurred during the first three months of combat flying. Acknowledging this reality, Norm decided that he wanted to be more fully prepared to fly the missions.

[Norm Komich] So, I took it upon myself to seek out who was considered the most experienced pilot in the unit. I found him alone at the Officers Club and he agreed to talk over dinner and later in his hootch until the wee hours of the night.

In those six hours I learned more than I had learned in six months of “training.”

Let me suggest, you can also be proactive as I was. Ask questions. Talk with your peers. “Hangar Fly” every opportunity you have. Read and absorb the messages of magazine articles. There IS a wealth of beneficial experience out there if you seek it out.

Personal Safeguards

En Garde

Tragic accidents have resulted from takeoff attempts with no flaps. For every accident there are hundreds of similar incidents of the same nature.

Consider the DC-10 crew that was distracted due to long taxi and takeoff delays:

[ASRS Report] When cleared to position and hold, the aircraft behind us asked if we needed flaps for takeoff. Score one for our pilot community!

One of the flight crew asked, “How could 3 crew members with thousands of hours of experience overlook this critical part of the takeoff process?”

As pilots, we need to develop our own personal safeguards.

Sage Advice?

[A Colleague] When taking the runway, check those items you’ll need to be safely airborne.

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)

Effective SOPs

Properly written, understood and used, standard operating procedures can be a great boon to safe flight operations. Their consistent use simplifies cockpit communications, reduces the chances for misunderstanding and allows for greater concentration on the unusual rather than the routine.

To be effective, SOPs must be concise and logically ordered. If they are incomplete, improperly sequenced or otherwise open to interpretation they lose their value for minimizing human error.

Equally important, SOPs should reflect a flight organization’s operating philosophy and be consistent with the organization’s stated goals. Adopting an aircraft manufacturer’s recommended procedures without review and critical examination may be unwise. Manufacturers are naturally concerned with liability issues and design shortcomings and apt to be self-protective in their positions.

Mythology

Icarus violated the only documented SOP of that aviation era.

Sterile Cockpit

Minimizing Distractions

“Sterile Cockpit Rule”

This FAA regulation prohibits any activity during a critical phase of flight that could distract any flight crew member from the performance of his or her duties. The rule attempts to enforce discipline in the cockpit and thereby lessen the possibility for error during “all ground operations involving taxi, takeoff and landing, and all other flight operations conducted below 10,000 feet.”

Captain Bob Mudge, a foremost CRM authority, suggests the rule should be expanded to cover all dynamic flight that he defines as all phases excepting cruise.

Although not covered by the regulation, pilots who fly general aviation aircraft should consider having their own appropriate sterile cockpit rule. Briefing passengers before flight on maintaining a professional atmosphere in the airplane will be well received.

Even non-pilots can become involved in the flight by being alert and pointing out other aircraft that they see.

There are times to sit back and enjoy the flight in the company of others. There are also times that demand the pilot’s full attention. Even the best need time to be “in the saddle” and adjust to changing conditions.

Anonymous Reporting

[Norm Komich] The US Navy understands “Honest Mistakes” to the extent that they have a section in their monthly Flying Safety Magazine Approach titled “ANYMOUSE” wherein pilots describe personal errors and spill their guts with no fear of punishment. Anymouse is a cartoon character whose identity remains anonymous.

This underlying attitude is the foundation of a genuine self-disclosure program that actively solicits safety concerns and disseminates the information so that others may learn and perhaps to avoid the possibility of future accidents.

It takes quality management to foster and maintain such a program.

Internal Reporting

Spreading the Word

Consistent with the concept of a Ready Room and pilots sharing knowledge of current safety issues, flight organizations are encouraged to employ internal reporting processes to effectively disseminate information related to standard, abnormal and emergency procedures.

NASA’s Flight Cognition Laboratory suggests potential report topics include:

- ATC experiences such as unusual approach restrictions, or encountered variations from published procedures

- Airport experiences such as unusual obstacles, lighting, or taxi routes

- Inconsistencies in standard operating procedures

- Aircraft operating anomalies

- Unusual in-flight encounters

Pilot reporting of personal errors and omissions is encouraged. For example, an unlimited variety of personal “goofs” that might have led to more serious consequences should be disseminated. If one pilot errs under a given set of circumstances then others may be similarly vulnerable.

Updating Checklists

[Norm Komich] While all checklists are NECESSARY, they are all too often NOT SUFFICIENT.

[Norm Komich] An internal reporting system would be the avenue to highlight and correct this oversight. Checklists begin at the aircraft manufacturer from a basic “template.” They then need to be refined to fit specific flight operations, environments, and corporate cultures. A nice theory, but how are such revisions accomplished in practice?

Safety Culture

The involvement of operational employees is fundamental to the success of any stated mission. The organization that challenges its employees, supports their professional development and helps to create an atmosphere of open communication is a force in creating and sustaining the safety culture desired. Realistic training, internal reporting, mentoring and peer interaction combine and feed on one another to increase the potential for success.

Intentional Noncompliance

Why do pilots intentionally violate procedures, rules and regulations? In a Safety Alert for Operators (SAFO), the FAA lists three elements that must be present:

- Motivation (Reward)

- High Probability of Success

- Absence of Peer Pressure or Reaction.

As pilots, we are mission oriented and determined to succeed. The Medevac mission in and of itself is particularly motivating. Of course, there may be economic incentives as well, including job security, influencing our decisions.

In learning this trade, we have taken chances that, in hindsight, might represent questionable choices. However, success tends to reinforce risky behavior and we must be on guard against improperly assessing any situation or our own performance ability.

Peer pressure is a powerful force that can lead to a constructive working atmosphere. Peer regard is another consideration. Pilots respect other pilots who seem to have it all together. By being consistent and acting professionally we, as individuals, have the ability to positively influence the behavior of our colleagues.

With regard to the elements cited, this SAFO describes typical violations found from analyzing aircraft accidents. The results include:

- Failure to conduct a stable approach

- Not maintaining minimum descent altitude/decision height or specified altitude

- Not electing to go-around

- Flight into severe weather conditions

- Operation with known equipment issues.

Flight departments can do a great deal towards minimizing PINC events by ensuring their policies and standard procedures are workable and consistent, and then insisting on compliance. Individually, pilots can do a great deal by assessing their own personal and professional behavioral standards, and then applying them without reservation.

Ethics

A Summary

Pilot Values

One survey asked, “What qualities are needed to succeed as a professional pilot?” The replies were many and varied and express the values that pilots of all backgrounds deem important.

In summary, the answers:

- Speak to the demands of the aviation environment—attitude; patience; perseverance; flexibility; grace under pressure.

- Speak to personal development—commitment to excellence; thirst for knowledge.

- Cite integrity as a core attribute—honesty; respect for others; a uncompromising code of ethics.

- Consider the ability to look inward—self-awareness/-motivation/-reliance—is considered essential in developing confidence and personal honesty.

- Emphasize the outward reaching character traits—sociability, people skills, humor.

- Cite passion, the one quality that stands above all others—a love of flying and the deep desire to be an aviator.

Each of us should be proud to be a member of this pilot community.

From the comic movie, Airplane:

With passenger-pilot Ted Striker (actor Robert Hays), a former Navy pilot (unqualified in type) reluctantly at the controls but attempting to bring the flight home safely, Capt. Rex Kramer (actor Robert Stack) is in the Control Tower to provide Striker with guidance and advice via radio communication.

Ethics

In this double glasses scene, Capt. Kramer discusses the flight’s situation with a colleague while bragging about his own military heroics. With pilot glasses as the perfect symbol of pilot cockiness, what could be more suggestive of a pilot’s inflated ego than wearing two?