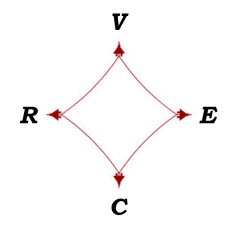

Leadership Diamond©

Courage:

Courage

[Peter Koestenbaum] To act with sustained initiative.

On Leadership Courage

Pilot statements from Professional Pilot Magazine and Aviation.Org subscriber surveys.

Confidence, Determination, Decisiveness, Taking Action, Maintaining Control, Patience

Pilot views on cockpit leadership are always informative and instructive. Pilots respect pilots who:

- check their egos “at the door.”

- have the ability to handle situations with comfort and presence.

- are at ease and are calm while analyzing complex situations and making decisions.

- don’t jump to conclusions

- make decisions that “maximize benefits and minimize risks”

- know when to say “no.”

- have the ability and self-confidence, in either seat, to admit mistakes instead of making excuses.

- are comfortable with critical feedback.

Independence of Thought

[Peter Koestenbaum] To have courage is to think for yourself. It is to reason independently when assaulted with conflicting opinions. It is to have clear and firm values, of which you are proud and which support you under stress.

To think for yourself means that you are steadfast in turmoil, in chaos, under stress, in doubt, in anxiety and guilt, in depression and anger, under assault and abandonment, in change, in ambiguity, in uncertainty. You are a fortress under siege, a ship in a storm, with experienced and calm commanders.

Control’s Mantra: Keep Flying the Airplane

The pilot’s first duty is to fly the airplane, to be in control of events as they unfold.

It is important for pilots to know their equipment and to adhere to thoughtful procedures. But pilots need to keep firmly in mind that their fundamental obligation is to fly the airplane, to be in command. Under pressure, events can pile up and create uncertainty. At times when things aren’t “right” it’s important to be in control and not drift along, hoping for the best.

Management control requires a predetermined mindset to act, to continue to fly the airplane..

Control Requisite: Decisive Action

It takes courage and self-confidence to act. Go-around when everyone ahead has landed? Climb to a safe altitude when it means delays and—worse—seems to reflect on your piloting ability? It’s easier to venture on, to see what happens and to hope for the best. To be honest, we’ve all done it, but it is a recipe for potential disaster.

Control Requisite: Deliberate Action

Hasty action can compound a predicament, leaving more desirable alternatives neglected.

A pause, however momentary, helps to maintain/regain control. Hesitation is nearly always in order before acting.

[Emperor Augustus] Make haste slowly.

[James Thurber] He who hesitates is sometimes saved.

Instrument Ticket, an Essential

[Norm Komich] Respect for the flight environment motivates proper preparation, not fear. Know the limits of your airplane, know your own limits, never exceed either one. Pilots should take time and build that confidence gradually. I’d also advise them to get real weather time with an instructor (classic mentoring), not just hood time.

Resisting Time Pressure

[Norm Komich] One of the common threads in aviation accidents is being rushed.

Without question, the folks at ATC can oftentimes put us in a situation where we are forced to hurry up. Last minute runway changes, delayed descents, expedited departures, etc. can all force us to rush and, in so doing, make an error.

Once, as I approached the active with a short taxi from the blocks, the tower cleared me into position and hold. I replied that I needed a minute to complete checklists and I would call them when I was ready. Tower responded that I could take my delay on the active, to taxi into position and hold and call when ready. I complied and, so help me goodness, 30 seconds later while half way through my checks, tower called and asked: “Are you ready yet, there’s an aircraft on base for your runway?” So, even though I tried to avoid rushing, I did rush, just to avoid forcing my fellow aviator to go around. What would you have done?

Then, there are time constraints. Curfews imposed (DCA), night restrictions as the sun is setting (Aspen), defined duty day requirements (Tenerife), all can lead to uncertainty and a rush to “beat the clock.” Diverting or cancelling may be necessary—don’t let it be your problem!

Maintaining Control

A flight may be faced with a compromising situation when an ATC clearance is received that is difficult or impossible to comply with. It’s time for action that is understandable and effective.

The simple communication, “Unable” (or “Unable to comply”), is the first step in addressing the predicament. This action statement will be most effective when it’s followed by a specific request. The result: control of the flight remains in the cockpit where it belongs.

Vision : Courage Polarity

Vision without action is simply daydreaming. It takes courage to act, to

make things happen. The diamond must be stretched in both directions

Courage: Digging for and Making Choices

The pilot selects and embraces a decision objective and an action strategy.

Some alternatives are obvious; others require some digging. Bob Mudge, developer of the Quantum cockpit management system, makes a crucial point when it comes to making choices:

[Bob Mudge] Judgment involves getting at the alternatives—identifying them in the first place—not just selecting from alternatives.

Digging for them involves more than considering favorable outcomes. It requires an appraisal of what can go wrong and preparing thoughtful counter measures.

Operational Inertia

A pilot approaches his destination airport for landing. The flight has gone well, and the airplane has been performing flawlessly. Bob Mudge says it’s easy to get caught up in what he calls “operational inertia”:

[Bob Mudge] This pilot expects to land. The tower expects the pilot to land. The passengers expect the pilot to land. The plane behind expects this pilot to land. ATC expects this pilot to land. All inertia is for this pilot to land.

The routine dictates resistance to any decision other than to continue and land. Bob continues,

To overcome operational inertia but also keep the landing objective forefront the pilot asks himself: “OK, what are the weaknesses in my landing strategy—what can I possibly encounter that might change my mind?”

Maybe there’s a runway problem, maybe a pilot familiarity problem, maybe a traffic problem, maybe there’s sand from icing day before that will reduce braking, maybe there’s a crosswind. The pilot actively seeks to find all possible weaknesses that might prevent him from landing, and for each weakness he comes up with a counter to it.

Exercising Judgment

[Bob Mudge] This judgment process is designed to find reasons that might be problems and then decide on how to counter these problems. Again, the pilot wants to land. This process is designed to ensure landing, not to find reasons not to land.

[Norm Komich] “The system,” the missing link. . . . Too often, pilot decision making is strongly influenced by the outside forces that make up the system.

Why is it so easy to make that decision after someone ELSE does it?

“Know your plane’s limits, know your own limits and never exceed either one.” Still pretty good advice.

Decision Making Perspective

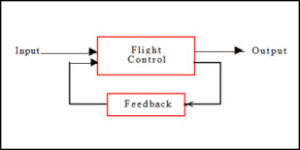

Decision making is characterized by the feedback loop that requires taking corrective action decisively and with precision.

Decisions are often multi-tiered with a number of strategies simultaneously in play.

Preparation

The best stress reliever is preparation; knowing your options simplifies the decision making process. Above all else, our first duty is to continue to fly the airplane and not be distracted from this fundamental task.

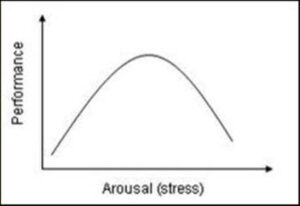

Deliberate Actions

Slow down and be deliberate. Know your personal capabilities and limitations and act accordingly—avoid the backside of the stress curve.

Caution

Needless to say, flying should be avoided when personal events and related stress become overwhelming since little performance reserve will remain.

On Leadership Courage

Statements from an address before the United States Naval Academy by the then Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates.

Courage

[Robert Gates] An essential quality of leadership is courage: not just the physical courage . . . but moral courage. The courage to chart a new course; the courage to do what is right and not just what is popular; the courage to stand alone; the courage to act; the courage to “speak truth to power.”

Self-Confidence

[Robert Gates] Self-confidence is still another quality of leadership . . . the quiet self-assurance that allows a leader to give others both real responsibility and real credit for success, . . . to stand in the shadow and let others receive attention and accolades. A leader is able to make decisions but then delegate and trust others to make things happen. It means trusting in people at the same time you hold them accountable. The bottom line: a self-confident leader doesn’t cast such a large shadow that no one else can grow.

Conviction

[Robert Gates] A necessary leadership quality is deep conviction. True leadership is a fire in the mind that transforms all who feel its warmth and transfixes all who see its shining light in the eyes of a man or woman. It is strength of purpose and belief in a cause that reaches out to others, touches their hearts, and makes them eager to follow.

Teamwork

[Robert Gates] On team-building, on working together, on building consensus. The time will inevitably come when you must stand alone. When alone you must say, “This is wrong” or “I disagree with all of you and, because I have the responsibility, this is what we will do.” That takes real courage.

Airmanship, in Summary

Performing to the highest personal and professional standards.

Being self-assured.

Exhibiting confident piloting skills.

Commitment

Who can forget the chilling exchange, FO to Capt, “We’re going in Larry,” followed by, “I know”? Air Florida Flight 90 crashed into the Potomac River, yet the power levers had not been fully advanced. The one action that had any chance of saving the flight was not taken.

Dramatic, but not an isolated incident; one that is, unfortunately, repeated.

An ASRS decompression incident recounts the failure of the 727 Capt, FE and Lead FA to don oxygen masks after loss of pressurization. The FO—inexperienced with only 10 hours in type—did use his mask, commenced an emergency descent, and saved the flight. Consider the scene: Capt, FE and LFA passed out in the cockpit, passengers all wearing masks in the cabin, FO at the controls.

These examples involve failures of basic airmanship. Nonetheless, if you were to quiz pilots on fundamental issues such as power application or countering the effects of hypoxia, they would pass their recurrent training. Still, other than our one reluctant hero, in these examples, all failed to perform as required.

What’s missing? As pilots we are drilled to obey the mantra, Keep Flying the Airplane, yet again and again a few fail to do so. We have the knowledge and, over time, understand and appreciate the consequences of failing to observe fundamental airmanship disciplines.

Knowledge, understanding, commitment. All are necessary but, at crucial times, the commitment can be missing. There is no group psychology here; we are talking about individual resolve.

Fly the Airplane

[Chuck Aaron] Never quit. Never give up. Fly it to the end.

On Spatial Disorientation

Recovery

Understanding Spatial Disorientation, a Video Presentation in the Cockpit Leadership Library

* Courtesy of Dan Gurney *

Recovery from Spatial Disorientation

Spatial disorientation can easily occur in the aviation environment. If disorientation occurs, aviators should:

- Refer to the instruments and develop a good cross-check.

- Delay intuitive actions long enough to check both visual references and instruments.

- Transfer control to the other pilot if two pilots are in the aircraft; rarely will both experience disorientation at the same time.

- Debrief on your erroneous perception and realize that it is a perfectly ‘human’ and ‘normal’ sensation (humans can’t help it). But, the condition is ‘not suitable’ for flying.

On Personal Commitments

Flight Debriefing

Blue Angels Briefing and Debriefing, a Video Presentation in the Cockpit Leadership Library

“I’ll Fix It!”

We all admire the skillful flying that military flight teams demonstrate. Few of us are required to demonstrate similar levels of precision, but we all can emulate the discipline these teams employ in preparing for each flight and in critiquing each performance.

Mental preparation is one key to the Blue Angels’ success as each pilot visualizes what he expects to see in flight. This routine exercise dramatically improves the pilot’s anticipation and situational awareness in flight. Another key is each pilot’s performance self-evaluation. The final video slide in ths Library video concludes: “Discipline, preparation and self-criticism are some of the attributes displayed in this presentation that has ‘lessons learned’ for all pilots in all aircraft types flying all variety of missions.”

The Blue Angels team was led by then-Commander Greg Wooldridge, a flight leader who emphasizes the importance of the debriefing. Regardless of mission, no flight is not over until the debriefing is complete, and not a flight goes by during which any pilot makes a mistake or two, however minor. To improve we need to learn from these experiences and make corrections.

In their debriefings each Blue Angel speaks to his own performance, tells the others the errors in technique or judgment he made during the flight and what remedial action he will take. At the end he’ll state, “I’ll fix it!,” a personal commitment both to the team and to himself.

What All Good Pilots Do

Summarizing a November 1996 Business and Commercial Aviation article by Capt. Bob Besco that remains a handy reference on personal commitment.

Capt. Bob Besco cites specific accidents and events as examples, but his main point is that professional aviators make flights uneventful. That is, professionals “apply superior wisdom, knowledge and judgment to avoid the situations that would require the application of superlative technical skills.”

After observing hundreds of flightcrews over his career, Bob Beso compiled a list of critical tasks that were found to be common to all good pilots. Differences in performing these tasks separate marginal pilots from the good.

A sampling of these tasks follows. Good pilots:

- Detect mistakes and anomalies soon after they occur (own errors, crewmember errors, errors by others).

- Correct and cope with mistakes and anomalies “immediately, gracefully and uneventfully.”

- Communicate their assessment of mistakes and anomalies without delay to fellow crewmembers.

- Stay mentally ahead of their airplanes and mission profiles.

- Say no to marginal operating conditions and resist coercion to “press on.”

- Maintain an attitude of openness to suggestions from crewmembers.

The ‘”good pilot’s task list” compiles and integrates tried and true ideas. Implementation is an individual choice and “the only cost is the personal commitment to go forward with applying these proven principles.”

Capt. Bob Besco provides us distinguishing character traits to cultivate so we may do “what all good pilots

do.”

On Vigilance

NASA’s Flight Cognition Laboratory’s Dr. Key Dismukes, Human Error or System Error: Are We Committed to Managing It? (Note: Specific aircraft accident review sare included.)

[Key Dismukes] Quoting USMC chief of aviation safety, “Fly smart, stay half-scared, and always have a way out.”

Vigilance

The “scared” reference may turn off some, but it does grab attention that “maintain awareness and stay alert” doesn’t quite pull off.

“Fly smart . . .”

- Be in control; don’t allow circumstances to determine outcomes. Be diligent and true to yourself—embrace the knowledge of others but think independently.

- Do not rush as few decisions require an instant response: Fly the airplane, but pause—hesitate—before taking an action that may be inappropriate.

- Decide on actions that allow you to maintain control and not permit perceptions and sensations to dictate your actions without corroborating evidence.

“. . . stay half-scared . . .”

- Avoid complacency; be involved and maintain that positive level of stress/anxiety that effective performance requires.

- Maintain awareness and not simply wait for events to take over; it takes courage to perform decisively.

- Know the aircraft’s limits, the flight’s limits and, above all, your own limits; keep tabs on them all and act accordingly.

“. . . and always have a way out.”

- Sage advice!

The Need for Increased Vigilance

[Key Dismukes] Pilot error is symptom not an explanation.

Trusting Your Gut

Taking Action

There are times when the stars don’t line up, that ambiguities surface and uncertainties exist.

Feedback is sporadic. Communications break down. Forecasts are unreliable. Things don’t “feel right.” Something from your experience or preparation is alerting you but you are unsure what it is.

You’ve done your homework. You’re good at what you do. So, in situations when doubt exists, “trust your gut.” It takes courage to act when facing uncertainty, but it is advisable to seek a safe haven and take the time necessary to sort things out.

[Eric Wickfield] The nagging feeling that something is not quite right is often unfailing in its precision. . . If you get a gut feeling, respond to it, don’t ignore it.

On Mastery

Harnessing Our Deepest Emotions

Combating Fear

[Mark Twain] Courage is the mastery of fear, not the absence of fear.

By extension, courage is the mastery of anxiety.

Facing Anxiety

{Peter Koestenbaum] It is critical to understand that anxiety is the key to courage, for courage is the decision to tolerate maximum amounts of anxiety. You should face your anxiety, you should stay with your anxiety, and you should explore your anxiety. . . . In general, management techniques, useful as they may be, are often more escapes from courage than effective tools to harness courage.

. . . Do not fear anxiety. Instead, allow yourself to feel it fully. You come out at the other end of the process strong and resilient, wise and mature. You prize the value of integrity. No significant decision, personal or corporate, professional or military, has been undertaken without its own existential crisis, the leader choosing to wade through rapids of anxiety, uncertainty, and guilt. It is such crises of the soul that give leaders their character and their potency. Dostoevsky said that taking a new step, uttering a new word, is what people fear most.

Courage

Live your passion.

Self Discipline

Personal Growth

In his CRM programs, Bob Mudge emphasizes the importance of personal growth:

[Bob Mudge] We ask pilots to look at their 5 Ps—Purpose, Philosophy, Policies, Procedures and Practice. Ideally, the individual’s 5 Ps should not in conflict with department’s or the company’s. They can be different, but not in conflict.

Self discipline is an essential element. It’s difficult to get pilots to write down their personal 5 Ps—for them it’s a new concept, new territory.

New territory, to be sure, and perhaps uncomfortable territory. But, as one noted psychologist once said:

[Abraham Maslow] After you get over the pain, eventually self-knowledge is a very good thing.

Bob’s 5 Ps embody, in a different format, many of the same cockpit leadership principles. Interestingly, NASA had listed the first 4 Ps, and Bob saw the need to add an essential fifth, Practice. This addition acknowledges the importance of reinforcing our technical, management and leadership skills, and the responsibility for maintaining proficiency.

Self-Awareness.

Each of us is at the center of our personal SHELL Model and, as PIC, has the responsibility of command, the authority to act and is ultimately held accountable.

How prepared are we? Have we equipped ourselves to accept these obligations?

It takes a certain level of courage to look inward and honestly evaluate our own performances. But it is true that that we learn best from our own mistakes, and it only makes sense to do so. Objective self-assessment has a liberating quality—it leads to personal growth and a fresh outlook that serves us well.

More Complex Decisions

As the SHELL Model checklist suggests, decisions are often multi-tiered with a number of strategies simultaneously in play. The diamond model allows for visualization of existing and potential conditions in a complex environment. The diamond depicts human decision making under flight conditions with both structure and flexibility.

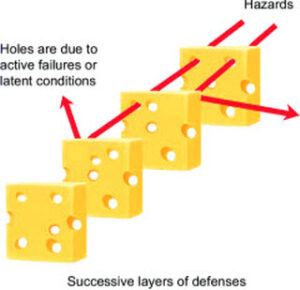

Latent Conditions, Active Failures

The Reason Model considers each organizational level as a barrier that may prevent a failure at a higher level from penetrating to a lower level. We are familiar how these barriers depicted as slices of Swiss cheese wherein each hole represents a failure. An accident occurs when holes in each barrier line up and all barriers are breached.

As we all know, the flight crew is the last line of defense!

Man in the Arena

Dignity

[Theodore Roosevelt] It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

On The Very Heart of Courage

Free Will and Responsibility

[Peter Koestenbaum] The very heart of courage, the philosophical core, is our human freedom . . . Freedom is a fact inside your heart. It is your most precious possession. It gives you power over your life. It gives you the benefits of being responsible for your existence and accountable for your life. Free will cannot be explained scientifically—only philosophically, poetically, religiously, or mythologically. Claiming your freedom is the ultimate secret for mastering your life. To discover your freedom inside your heart is an exuberant experience of both exhilaration and hope, and that freedom can never be extinguished. Heroes have exercised this freedom at the risk of life itself. True love means to surrender that freedom to another . . .

From freedom follows the power for initiative. The leader is a self-starter. Leaders energize themselves; they do not require external sources of enthusiasm. They know that to be human is to be a creator, to have the ability to start something from nothing. The creation of the world, a theme in all of the world’s mythologies, is the cosmic image of our subjective initiative—a cosmic metaphor for our innermost truth.

Pilot Attitudes and Mindsets

United Airlines’ Skyliner Survey

Pilot responses related to Courage:

- There’s almost nothing that needs to be done in a hurry in an aircraft.

- Pay attention to your sixth sense. If something feels wrong, it probably is.

- If you are getting rushed or overloaded, slow down even if it means delaying pushback, delaying takeoff or even holding.

- Return to basics if you become confused.

- Maintain a healthy level of suspicion.

- Avoid complacency; the minute you think something won’t hurt you—it will!

- Be especially vigilant when everything is going well. . . . You must resist the tendency to become complacent when everything looks normal.

- Don’t become complacent; sit on the edge of your seat; never take anything for granted; never become relaxed; question everything; stay alert.

- The way to be safe is never to be comfortable.

- A pilot must be able to adapt; no two situations are the same.

From the comic movie, Airplane:

Passenger Ted Striker (actor Robert Hays), a former Navy pilot, is required to take the controls because the aircraft’s pilots are incapacitated. Striker is not an active pilot, haunted by earlier combat encounters, is certainly not qualified and completely unprepared for to fly an aircraft of this type, especially during stormy conditions at night.

Courage

In this scene, Striker’s emotions are evident as he resolutely does his best to save the flight and land the airplane.