The Cockpit Leader

Federal Air Regulations state:

The pilot in command of an aircraft is directly responsible for, and is the final authority as to, the operation of that aircraft.

This statement is clear and concise. It leaves no room for ambiguity. It is not open to interpretation.

The regulations express an individual freedom conferred on all pilots who assume command without regard to age, experience or type of aircraft flown. This freedom requires assumption of responsibility but also grants the right to act decisively when performing the duties of command.

To command is to lead. How do we prepare for this responsibility? How do we ensure leadership qualities are developed, nurtured and sustained? Cockpit Leadership will strive to provide meaningful answers to these and similar questions.

Cockpit Leadership Requisites

Cockpit leaders maintain awareness of all aspects of their flights including the changing and dynamic flight environment in which they operate. Due to preparation and foresight they are confident as they track progress and develop strategies to complete tasks and address anomalies that may arise.

Knowledge of the aircraft and its systems performance and human factors limitations are leadership prerequisites. In addition, the members of the cockpit crew ensure that their responsibilities are clearly defined, that agreement is reached on strategies to be pursued and that potential conflicts are resolved. Even flying alone, the pilot-leader values and respects the contributions of aviation personnel who help make safe flight possible.

In this three-dimensional world, pilots form mental images of situations that exist or may exist during flight and project alternative solutions to a difficulty should one materialize. Pilot-leaders face reality and think and act with determination and integrity.

This Cockpit Leadership undertaking will expand upon these leadership requisites by presenting a mental framework based on sound leadership principles and by applying this structured process to the operational flight environment.

Introducing the Leadership Diamond©

Individual leadership traits are mentioned in inspiring graduation speeches, but words and slogans are inadequate and empty in the heat of the moment. Pilots assess developing situations and act strategically according to their experiences, training and beliefs.

On reading the About page, you will get see that Dr. Peter Koestenbaum granted the use of his Leadership Diamond© model with its strategic approach to leadership thinking for this effort to promote safe flying.

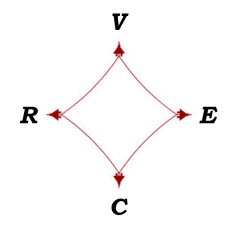

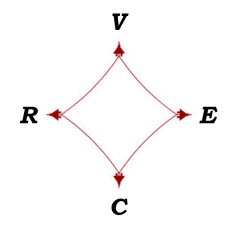

In this Cockpit Leadership presentation the leadership strategies—Vision, Courage, Reality, Ethics—are developed and applied to flight situations. Please take a moment to think about the scope of these disciplined strategies—every oft-cited leadership trait is embodied in one or more of the diamond’s strategies.

The Leadership Image

The interrelationship of the four leadership dimensions is shown by Peter in his simple but effective mental model:

The Leadership Diamond©

Vision: to see the larger perspective

Courage: to act with sustained initiative

Reality: to have no illusions

Ethics: to serve based on principled standards*

*Slightly expanded to reflect the operational flight environment.

The diamond image represents the potential scope and quality of an individual’s leadership ability. In fact it represents the leader’s mind at work with each of the diamond’s forces—vision, courage, reality, ethics—thrusting outward and keeping the diamond taut. Consider this mental image as a flexible membrane, alert and active, with all the forces equally balanced.

The balance of forces is maintained since the pilot-leader knows that vision without courage is dreaming, blind courage is foolhardy and ethical violations place others at risk.

Applying the Leadership Model

Within the subscriber Hangar 13 section of Cockpit Leadership, the many dimensions of leadership are considered in a variety of flight circumstances. In each instance the four Leadership Diamond© strategies are described in detail accompanied by related thought processes and actions.

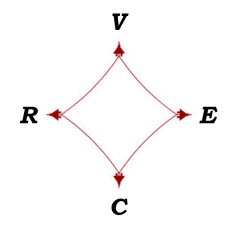

As one introductory example, please read again the opening FAR statement, “The pilot in command of an aircraft is directly responsible for, and is the final authority as to, the operation of that aircraft.” Its visual diamond presentation is:

PIC

Vision: My goals are clear

Courage: I claim the authority entrusted in me

Reality: I am accountable

Ethics: I am responsible

When forming this mind-view every pilot should pause to cherish the freedom granted when climbing into the cockpit.

This basic example gives an indication of how the Leadership Diamond© model might be employed. In the Hangar 13 subscriber section the diamond will be applied to a number of aviation issues or situations including those related to the aircraft and its systems, the flight environment, pilot judgment and decision making, risk management and incident or accident critiques.

It is important to emphasize that the application of the Leadership Diamond© is fully compatible with and may well enhance CRM and risk management pilot training programs or SHELL and Reason model applications and concepts.

Further Thoughts

Pilots honor and respect the freedom they enjoy in flight and are confident facing the attendant risks. When gaining experience in instrument flying conditions, they learn to picture accurately and in detail their aircraft’s performance, progress, attitude and position from reading and understanding their flight instruments. In short, pilots paint mental images and visualize present situations and those that may lie ahead.

The Leadership Diamond© is a natural fit. It brings form and substance to the pilot’s actions, decisions and projections. In flight the diamond use is specific. Situations are evaluated and choices made. Risks are analyzed and mitigations planned. Decisions are made and actions taken.

The leadership mind is flexible and adapts to new and changing situations. A diamond forms naturally as a mental image for each event or circumstance. A situation may be resolved or may later be recalled at appropriate times until there is a final resolution. The cockpit leader maintains situational awareness and is comfortable visualizing a variety of interrelated diamond images.

Subscribe!

The diamond is not simply another tool in a pilot’s safety toolbox. In terms of cockpit leadership and the development of flight strategies, it is the toolbox.

This website is established for pilots of various experience levels. Please be encouraged to click on the yellow Subscribe button, answer a brief series of questions related to flight qualifications and experience, establish a user name/login and go to the Hangar 13 subscriber section.

Join your colleagues in sharing your interests and experiences.

[Press ESC to Close]

by Dan Gurney

This paper is posted on the ICAO website, and is found at: Celebrating TAWS “Saves”.

The excepts below are its Introduction and Conclusion sections that serve to provide a preliminary view of the scope and importance of CFIT avoidance. Please note that the paper also includes an Addendum.

Introduction

This paper reviews six approach and landing incidents involving controlled flight towards terrain (CFTT). All had the potential for a fatal accident, but this outcome was avoided by the Terrain Awareness Warning System (TAWS) alerting the crews to the hazard. The following review of the circumstances and precursors that lead to these incidents indicate that the industry still has much to learn or remember about how to identify and counter latent threats particularly during the approach and landing phase. In addition, the industry still has to maintain focus on the problems of human error, particularly those situations which have potential for error or containing threats that were either not identified or were mismanaged. There were many errors in human thought and behaviour. Several common features were identified; most had been seen in previous controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) accidents. The objective of this paper is to promote the values of sharing safety information. None of the operators, aircraft, or crew involved in these incidents is identified; indeed the

review and subsequent communication processes do not require these details in order to be highly effective safety tools. Thus this paper provides an example of how successful confidential reporting and local investigation can be providing crews submit safety reports and the operators undertake an open, ‘blame free’ investigation.

Addendum

The Addendum reviews two additional CFTT incidents that cover three night visual approaches.

Conclusion

The incidents described in this addendum involved timely TAWS warnings, but these were not heeded by the crew. In both events the normal margins of safety were eroded by human behaviour – inaction or inappropriate action after a warning was given. This resulted in undesired states – “being as close as you would ever want to be to an accident”.

The industry has enjoyed great success in reducing the contribution of CFIT to the accident rate, but there is no room for complacency. We must ensure that modern technology does not just cover over the cracks, but in conjunction with systematic and organisational safety activities, it provides a lasting change in our operations.

TAWS incidents are reminders of the continuing threat to safety from the hazard of CFIT.

Published Article by Bruce Mayes

Every student pilot who gets through the lectures on lift and drag, the permutations of weather, or buttonology” for new-age avionics, knows the struggles of completing basic ground school. Mastering the knowledge required to successfully pass the written (knowledge) exam for a pilot certificate or rating is a huge undertaking.

When combined with the bookwork, the many steep learning curves and performance plateaus the student pilot experiences are sufficient to weed out those who lack the genuine desire to become a pilot. Achieving this status is not taken lightly by those in the midst of the learning cycle.

Privileges and Responsibilities

Once the much-coveted document is in hand, pilots are free to exercise the privileges of that certificate or rating. What we need to understand is that, as with citizenship in a country, the privileges that come with admission to the world of aviation carry responsibilities. Abuse of those privileges can result in losing them. Medical issues aside, the most common way to lose piloting privileges involves some version of “stupid pilot tricks.” Why would a pilot who has invested so much time, money, and energy to earn a certificate or rating blow it all with one foolish act?

Is There an Antidote?

Unfortunately, we do not have a reliable filter to weed out the proverbial “bad apples” before they kill or injure others. We rely on individual responsibility. We also rely on a higher standard culture because regardless of aircraft size, each individual with a pilot certificate has been given the trust and responsibility to operate an aircraft, and to carry passengers.

If you follow the policies, procedures, and rules, and if you do so with the knowledge and skill required to be a good pilot and a solid aviation citizen, you will most certainly be safer. Guard your privileges through your own behavior, and never let company or peer pressure force you into acting in a way contrary to those principles. Guard them as if your future depends on it, because your flying future—and maybe your life—does.

A status that is earned and respected. Airmanship is identified with performance quality based on specialized knowledge and experience.

Requisites

The airman possesses confident piloting skills, sound judgment and a strong sense of personal accomplishment and well-being. Airmanship is the full integration of the piloting to leadership skill sets.

Qualities

Personal character, enthusiasm, and the demonstration of piloting, management and leadership ability on every flight are the attributes that distinguish individual airmen.

Respected Definition

[Tony Kern] Airmanship is the consistent use of good judgment and well-developed skills to accomplish flight objectives. This consistency is founded on a cornerstone of uncompromising flight discipline and is developed through systematic skill acquisition and proficiency. A high state of situational awareness completes the airmanship picture and is obtained through knowledge of one’s self, aircraft, environment, team and risk.

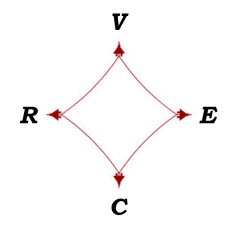

The Airman’s Leadership Image

Airmanship

Vision: Reasoned judgment to accomplish flight objectives

Courage: Self assurance; confident piloting skills

Reality: Specialized knowledge, proficiency; high situational awareness

Ethics: Personal character; uncompromising flight discipline.

Published in August 2006 by Captain Phillip H.S. Smith, then vice-chair man of the Roy al Aeronautical Society’s Flight Operations Group.

The cry that aircraft commanders have had their authority taken away from them is not a new one. It was certainly being voiced in the early ’70s and no doubt before. Legally it is quite clear that this is wrong. In the UK that authority currently derives from and is laid down clearly in JAR-Ops 1.085 (f) which starts: “The commander shall:” and continues in subparagraph 3 “have authority to give all commands he deems necessary for the purpose of securing the safety of the aeroplane and of persons or property carried therein;”. This is clear and straightforward language: “give all commands” and “he deems necessary.” No question there of giving only those commands that won’t cost too much or asking someone else whether they consider a command necessary.

That being the case, why is the contrary perception so widespread? Is it that the perception is faulty? In any particular case, it can be hard to judge whether authority was exercised as it should have been, and in any case such a judgement is inevitably an exercise of hindsight, laced with information and often lengthy analysis not available to the commander when the decision was made. However, I think most people would agree that incidents in which there is the appearance of a commander’s judgement having been, at least, unduly influenced by outside agencies are more common than they were in the past.

Influence of Communications

Partly this is a consequence of better communication. When Ernest Shackleton left South Georgia on 5 December 1914 on his abortive expedition to cross Antarctica via the South Pole, he had no possibility of communication with anyone beyond his crew until he reached a whaling station on South Georgia in May 1916, nearly 18 months later. Accounts of his character suggest that anyone trying to usurp his authority would have received a dusty reply but, in the absence of communication, there was no such possibility. Excellent communications allows a commander to seek information and advice if time is available but it also allows operators or outside agencies to attempt to compel a particular course of action.

It is too much to expect even the best informed and most carefully briefed commander to have committed to memory or have at his fingertips all the information that might be of use in every conceivable situation. A prudent commander faced with a critical situation will acquire all relevant information he can in the time available before he makes a decision. He will probably want to seek advice from specialists in areas, such as security, where such specialists have access to sources not available to an aircraft commander. But neither the commander nor the source of information or advice should forget that it is no more than that. A request for information must not be taken as a request for instructions.

Management Directives

T he operator, personified by the commander’s managers, may try to dictate what their commander should do. This is understandable in a world in which a manager’s next pay rise and promotion may depend on the outcome, and especially the perception, of a decision made by someone they manage. Sometimes an operator’s standing instructions may point to a course of action that is inappropriate in the circumstances on the day. Outside agencies such as security authorities may also feel that they have the right to compel a particular course of action. The responsibility they bear is heavy and their priorities are wider than those of the commander of an aircraft. Nevertheless, neither the operator nor any other agency can take over command of the aircraft.

As pilots are fond of saying, ‘at the subsequent enquiry’ the commander will be held responsible for a decision and its consequences. When a decision based on advice received from outside is called into question, it will inevitably be asked if undue weight was given to the advice. Advice and information that turns out to be misleading may be offered in mitigation but it will not absolve the commander of his responsibility. Nor will those who supplied the advice or information take responsibility for the decision, though they may have to bear the responsibility for the information or advice offered. Commanders must not forget this. If they receive what seems to be an instruction, the commander bears the responsibility for complying with the instruction. The commander’s judgement should be informed by the best information and advice available in the circumstances but only the commander can make the decision. If advice indicates a course of action which is wrong in the judgement of the commander, then it is the judgement of the commander which must prevail. That is what an aircraft commander is paid for.

Analysis by Hindsight

T he scrutiny of decisions with hindsight is damaging. It is an inefficient method of management, because it leads to unwarranted conclusions. It may damage the confidence of a commander and engender hesitancy to make a decision on the next occasion. This is not to say that when a critical decision has been made, whatever the outcome, it should not be subjected to careful examination. The publication of the details of incidents and their outcome, together with decisions made along the way, contributes greatly to the safety of aviation. What must be avoided is the suggestion that a different decision would have been ‘better’ on the basis of hindsight and analysis carried out with unlimited time and information not available to the commander on the day.

Conclusion

So the authority of an aircraft commander has not been taken away but it may be given away. Sometimes perception becomes reality. If commander s believe that their authority is reduced they will be more reluctant to exercise that authority. This is dangerous. Aviation and in particular the aircraft operator, needs Captains who are not just competent to make decisions but ready to exercise authority when necessary, particularly when difficult and speedy decisions are required. Aviation cannot be safe without them. Commander s must take command.

Submission by David St. George

At the heart of safety is the element of surprise and changing conditions the pilot inevitably encounters and must analyze on the fly. As an instructor and DPE, my quest is to illuminate the bipolar pitfalls of either a too rigid a plan in the face of changing circumstances, or a failure to plan carefully because “it will all change anyway.” General Eisenhower, a respected strategist, is quoted as saying, “Plans are nothing, planning is everything.” In the training world we strive to plan carefully and then strip away resources or alter flight reality to test and hone pilot judgment.

Every plan undertaken in aviation must contain the firmly held understanding that it is only a hypothesis, an enterprise subject to change from its inception until the chocks are in place. Too often a pilot refuses to “see reality” and continues despite a new set of circumstances for which the plan was not designed–a form of “wishful thinking.” Pilots must embrace change and flexibility to be able to respond to dynamic conditions.

Like quarterbacks or military commanders, pilots need to develop the savvy to be able to continually read situations rapidly, assess the risks and act appropriately (then evaluate, reboot and continue the process). Another necessary skill is to develop a process of self-questioning that I call “angel on the shoulder.” The pilot, although engrossed in a complicated and detailed operation, must retain the ability to move attention from the immediate task and observe the bigger picture from a more objective viewpoint. Asking the angel on my shoulder, “Does this make sense in relation to my overall standards and objectives?” begs an answer.

These two viewpoints, analogous to the close-up and wide angle lenses on a camera, must constantly shift and, like an instrument scan, never fixate. Another comparison of the two would be the warrior (intensely engaged in the “here and now”) and witness modes of action/inaction in the martial arts. These ideas and concepts are ones from the trenches where I use and teach them in everyday flying.

–David St. George

Flight Incident

In seeking “lessons learned” we often report on the lack of airmanship skills and human failings that lead to undesirable outcomes. The good stories, those that tell of flight crews averting disaster due to exceptional cockpit skills, are hard to come by. High quality cockpit performance is seldom reported and rarely acknowledged. But, here’s one:

The Challenge

May 11, 2009. O. R. Tambo Airport (JAJS), Johannesburg, South Africa. Night takeoff in good weather, Boeing B747-400. From a wire service, BA 747 Crew Praised after Slats Cause Near-Stall on Take-Off:

“At 167kt on the take-off roll, fractionally below rotation speed, the leading-edge slats automatically retracted, after receiving a spurious indication of thrust-reverser activation.” Lift was significantly reduced and “the stick-shaker immediately engaged, warning of an approaching stall.” Significantly, “the flight-deck crew had no indication or understanding of what had caused the lack in performance of the aircraft.”

The Response

The crew responded appropriately and without hesitation. “Instead of following the typical climb profile, the first officer controlled the aircraft through the stall warning and buffeting by executing a shallower climb, while the commander supported the maneuver by calling out heights above ground.” After becoming airborne, the landing gear was retracted and the leading edge slats redeployed automatically. The aircraft slowly regained safe flying speed later landed safely and uneventfully at the departure airport.

Team Leadership

The technical details will intrigue many readers, but interest here centers on the actions in the cockpit and the leadership traits exhibited:

**Vision: “I will continue to fly the airplane.” Aviation’s first and only mantra; little else is important at this time.

**Reality: “Something is terribly wrong.” I don’t know what is happening; I am being challenged.

**Courage: “My actions are deliberate but cautious.” I will perform to the best of my ability; I am calm in crisis.

**Ethics: “I accept this responsibility.” My duty is to all aboard; I expect to be held accountable.

It is not suggested that these were actual thoughts by the pilot at the controls. There was little time to formulate precise thoughts during those crucial 23 seconds. However, based on preestablished principles, they may represent the mindset of a professional, a pilot-leader who is comfortable with him and confident in his ability.

The crisis was immediate—there was little forewarning—and the pilot flying responded as his core beliefs dictated. He successfully flew the aircraft at the very edge of its performance envelope until essential lift was restored. Unfortunately, we do hear of instances when the right seat passed the mantle of responsibility with little warning, disrupting continuity and often worsening the situation.

Much can also be said for the captain’s leadership during this predicament. In addition to keeping the individual roles defined, he managed risk by fully supporting his FO and making appropriate call-outs, exhibiting similar leadership traits. So much for the “followership” jargon! The flight crew performed superbly, both individually and as a team.

Submission by Norm Komich

When the NY mounted policeman who responded to the Times Square Bomber was interviewed, he simply stated: “The training kicked in and I just did what I was supposed to do.”

This simple statement has very powerful undertones for the aviation community. I heard the following “war story” about an Air Force pilot who was in training to earn his wings:

“I was solo in a T-33 (single engine jet trainer) on a low level mission when the engine just flamed out. It was like a neon sign appeared in front of me. 1) THROTTLE—“IDLE”; 2) FUEL SELECTOR—“ON”; 3) IGNITION—“ON”; ETC. All that training on the ground kicked in and I just responded; I did NOT have to stop and think about what to do.”

One of the most influential experiences I ever witnessed was when I sat in on a mission pre-briefing of a flight of four A-10s. The briefing was conducted by a briefing officer, not the flight lead, and he covered every detail of the entire mission, including slides of various legs of the route. When this portion of the briefing was finished, he switched to a series of slides on Emergency Procedures, pointing to a pilot who would then recite the defined actions step-by-step. I vividly remember leaving that briefing impressed, particularly when comparing it to my own preflight briefings. Even though a single-seat fighter pilot has no one else to rely on, as I did, I should not be deterred from being equally prepared.

My final “war story” is about George Tucker, a Marine test pilot who went on to test-fly for NASA where he was current and qualified to fly 17 different aircraft from a B-52 bomber to a Helicopter Cobra gunship to an F-18 fighter. I had the opportunity to ask him how he did it, and his answer was intriguing. He said that, for whatever reason, there were certain limits, procedures, systems, etc. that he naturally remembered for each aircraft. But for the rest of the items he made up 3” X 5” flashcards for a particular aircraft that he would go through prior to each flight. I think of this discipline as “loading up the short term memory” before flight.

What are the “cockpit concepts”? Hopefully one is the motivation to ask yourself that, on any given flight, are you prepared to spit out the Memory Items like those A-10 pilots could? Another is to ask whether you are able to apply the systems knowledge when needed, as George was able to do. I certainly hope so, but I also worry that in today’s bottom line culture in aviation, training is getting the proverbial short end of the money stick. For example, my last training in the A-320 was abysmal, oriented only to “passing the checkride.” My basic learning took place while flying to generate revenue and, in wanting to learn more, I had to do it on my own. I fear this scenario is too commonplace today. Perhaps the reliability of today’s highly engineered and over-automated aircraft and engines has seemingly reduced the practical need to know. Nonetheless, the threats to flight safety are still present.

My concluding observation is that training all too often stops with the checkride. Captains typically take two a year and First Officers one. How much of your last checkride was “checking” (displaying competence for various maneuvers) and how much was “training” (learning something new)? I can hear the cash register ringing in the background again as the bottom line dictates “. . . in compliance at the least cost.” The burden of this philosophy shifts the learning curve from the company to the individual pilot so when the “training kicks in” it just might be your own personal learning that saves the day.

Submission by Norm Komich

Since the dawn of aviation, aircraft accident investigators have focused on “the man, the machine, and the environment.” I would like to add a fourth—“the system”—and consider it the “missing link.” Too often, pilot decision making is strongly influenced by the outside forces that make up the system. These forces are generated from a variety of sources including ATC, corporate cultures, and business or personal commitments. All tend to influence pilots to do things that under other circumstances they would not do.

Simulators are considered the ultimate training tool and they are wonderful for teaching procedures and stick and rudder skills. But no matter how realistic they are, they can NEVER duplicate running out of gas, or being pressured to get home for a special event, or having a dying patient on board, or working for a company that fires pilots for not pushing the envelope. To not acknowledge the role such circumstances play in our decision making is a huge mistake.

I have always advocated that, “When you are down to only one option, you have given up your “professional” status and reverted to being an “amateur.” Sometimes the system will force us into a “one option” only circumstance, but I fear that too often we put ourselves in that situation. When I see “freezing rain” in the forecast I picture that old B&W movie that showed the ice accumulating on the wing at the rate of over 1 inch a minute. Then I remember being #2 for takeoff at JFK in a heavy snowstorm behind a 747 as the snow blew laterally across the runway. It was nighttime and the tower cleared the United flight twice for takeoff before this crusty voice came on the radio and said, “I think we’ll go back to the gate and wait awhile.” And we did the same thing. Why is it so easy to make that decision after someone ELSE does it? And when you absolutely, positively have to be there, why is it so difficult to leave a day early so that you avoid any travel disruptions that force the wrong choice?

The best advice I ever received in my 40 years of flying was from my squadron commander at my first PIC upgrade when he admonished, “Know your plane’s limits, know your own limits and never exceed either one.” Still pretty good advice.

Submission by Doug Harrington

For several years I had the privilege of working closely with the men and women who operate the control rooms of our country’s nuclear power plants. In addition, I work with the operators who man the control centers that maintain our electrical power grid. I “teach” teamwork to these crews, but in the process, I have learned more about teamwork from them than they ever learned from me.

One of the questions I am often asked by the crew members is, “What is the one major thing we need to work on to look good as a team?” First I have to get them to understand that teamwork training is not about “looking good.” Crews seem to think of teamwork as some specific, observable behavior that will impress those who evaluate their performance. The class is more about how you function as a team and as a team member during a time-critical, emergency situation. It is about each person’s role in assessing a situation, making good decisions, and accomplishing the tasks necessary to solve the problem.

My wife once suggested I write a book about all the things I had learned during my years of flying for the Navy and my years of working with control room crews. I gave up the book idea pretty quickly, but it did get me to thinking about what I had learned from these crews. So, just in case, I came up with a list of chapter titles and called them my “Seven Undeniable Truths.” I will share a couple of those chapters that I believe fit this topic of the importance of defining roles in a crew.

Number one is, “Human error can be caught before it becomes consequential.” The second is, “It is not possible for an entire team to ‘go stupid’ at the same time.” Both of these have to do with the importance of every crew member being aware of their responsibility to catch mistakes or errors and stop them before they become consequential.

Over the years of working with control room crews in simulators, I have observed a number of crews go down in flames during an emergency scenario. During the rather detailed debriefing, we nearly always find at least one, if not more, of the crew members had a “bad feeling” about the direction the crew was taking but failed to say anything. Or, a crew member had a significant piece of information (I call this the Silver Bullet) that, if communicated, would have put the crew on the correct path to success but failed to verbalize that piece. Those experiences got me to thinking about “why” crew members are so reluctant to step in and save the day.

Some of the excuses I often hear for why a team member kept his thoughts to himself have to do with that person’s beliefs about what will happen if they speak up. One of the most common excuses is the fear of being wrong. “What if I question something, and I look stupid.” The fear of sounding stupid. Another very common problem is over confidence in the senior person. “They must know what they are doing.” One of my favorites is, “I thought you already knew.” One rookie operator even went so far as to say, “If I knew, you had to know!” Experiences in our past have helped develop these beliefs, and more recent experiences may have helped to validate them.

“Culture” is a term I use to define this phenomenon. I define culture as “the way we do things around here.” When you first join a company, team or crew you spend the first few days or weeks trying to figure out your role in this new organization. You do that by observing others or by getting personal feedback from your peers and from those above you. Over time, you begin to learn the culture and to define your “role” in the team. I am not talking about job description here, but rather the way I believe I am expected to behave in certain situations.

Let me explain the role thing in this way. Your role in my team is what I think it is, and if you are not fulfilling that role, we have the potential for a problem. An old friend of mine, a retired 767 Captain, related to me how he would deal with this problem of confusion over roles. When he would climb into the cockpit and meet a First Officer he had not flown with before, he would say something like this, “You don’t know me and you don’t know how I fly. So, if at any time you are uncomfortable with what I am doing, you have got to tell me.” He had just defined the First Officer’s role. He needed him to stop errors before they became consequential.

Once you have defined that person’s role, you have to be willing to live up to your end of the bargain. If just once you punish your teammate for questioning your actions, you have just redefined his or her role, and most of us learn very quickly.

In my classes I encouraged crew members to sit down with each other and talk about expectations of roles. What does each crew member believe the others are doing for them. If I believe you are backing me up and you are not, we have a problem. If I believe you will confront me if you believe I am wrong and you have learned to keep your mouth shut, we have a problem. You may have brought an old culture, or belief, to our team from a previous experience that needs to be redefined for you to be effective in your new team.

My belief is that crews do not clearly define roles, and I ran an exercise at one nuclear plant to prove this point. I put the reactor operators (ROs) on one side of the room and the senior reactor operators (SROs) and Shift Manager on the other. I gave each team a large sheet of chart paper, and I asked the ROs to write down, very specifically, all the things they believed the SROs expected of them during an abnormal or emergency situation. I asked the SROs to write down everything they expected of the ROs. Happily there were a lot of similarities in the two lists, but there were enough differences that made for some very interesting discussions.

I believe we have lost some understanding of the roles and accountabilities of crew positions. We have become too focused on behaviors and the “correct ways of doing things.” If you are a flight crew, I encourage you to clearly define the roles of each crew member. And remember, it is not possible for an entire crew to go stupid at the same time. Someone knows something.

Submission by Doug Harrington

Several years ago, a couple of PhDs spent some time aboard a US Navy aircraft carrier with the intent of finding out how the Navy was able to take a bunch of young men, average age 19 to 20, and get them to perform so effectively and consistently in a pretty hostile environment on the flight deck of a carrier. I could have saved them a lot of time and effort because I had spent more than a year of my life immersed in that environment as a Naval Aviator and was aware of the answers.

Role Awareness.

Sitting in the cockpit of my A-6 Intruder on the flight deck of the USS Nimitz waiting to taxi onto the catapult, I had plenty of time to watch and study the amazing performance of these “kids” and wondered the same thing. How do we manage to get twenty plus aircraft launched and recovered back on that flight deck every two hours, day and night, with very few mistakes? The answers really are simple. First these “kids” are disciplined and well trained in their jobs. Second, and most importantly, each person on that flight deck has a clearly defined role to play in what must appear like chaos to outside observers. While it may be chaos, it is well managed chaos. Not only does each person understand and carry out their role, they are also aware of the other roles with which they must coordinate in the safe launch and recovery of tactical aircraft.

“Shirts,” and Critical Functions.

The other thing that helped on the flight deck was each critical function wore a different colored jersey, referred to as “shirts,” to designate their specific role. When my Bombardier-Navigator (BN for short) and I approached our aircraft, we were met by a young sailor, a Brown Shirt, who was our Plane Captain and had prepared our Intruder for our arrival. Once in the cockpit with engines running, we waited for a Yellow Shirt to begin our taxi toward the catapult. During taxi, I could see Green Shirts, squadron maintenance personnel, checking over our aircraft while Quality Assurance personnel in black and white Checkered Shirts did final overall checks to ensure the Intruder was ready to go. Well defined roles, each knowing what to expect from the other Shirts, helped them perform flawlessly every day. Did we make mistakes or have mishaps during flight operations? Of course. One wrong move, moving too soon or too late, or confusion over roles could cost a young man his life.

Crew Discipline.

Launch and recovery operations were a well-orchestrated performance carried out by a highly trained and disciplined crew. The same can be said for the cockpit crews, the carrier air traffic controllers, and the Landing Signal Officers (LSOs). Each of us had specific roles and accountabilities that, when performed well, allowed us to land back aboard the carrier safely.

Teamwork Lesson.

Much of what I have learned about teamwork that has stayed with me over the years can be attributed to my days as a Naval Aviator flying the A-6 Intruder. Some of the lessons were learned the hard way, while others were part of a deliberate attempt by my first BN to get me in line as quickly as possible. When I first joined my squadron as a “new guy,” I was teamed up with Stony, who had already been in the squadron for a year. Stony’s first objective was to make sure he had a pilot who could function in a two-man cockpit since everything prior to the A-6 had been single seat where the pilot obviously does everything. He first wanted to know how he could help me when flying missions or during emergencies. Everything he offered to do were things I had been doing myself for a long time such as handling the radio communications, dealing with emergency procedures, or simply flying an instrument approach. I just told Stony to do his BN stuff.

On one of our first night, low-level flights together Stony decided to test my teamwork skills (CRM was not around then). While skimming across the earth in the dark at 500 feet and 500 knots, I suddenly felt an unfamiliar thump in my ejection seat. When you are strapped to a chair that is loaded with explosives and rocket motors designed to throw you out into the cold night, a thump will get your attention. Fortunately, nothing happened. I can’t really tell you why, but I did not say anything to Stony about my experience. Maybe I didn’t want to worry him, or I was used to handling bad things by myself. My seat went thump about three more times during the 1.5 hour training flight. Not a word to my BN.

While walking back into the hangar that night, Stony inquired about how I thought everything went during the flight. I told him I needed to have Maintenance take a look at my ejection seat because I felt a thump several times during the flight. He wanted to know why I didn’t tell him about it during the flight. That took me by surprise, and all I could say was, “It was my seat!” I will never forget his response to that. “Do you realize that if your seat were to unexpectedly eject from this aircraft I don’t have a ride home?” I guess I hadn’t given that much thought, but Stony had just given me my first teamwork test and I had failed.

Lessons Learned and Applied.

I took this Navy education and began a 28 year career training control room operators in nuclear power plants. Again, the importance of well-defined roles emerged as a very critical element in a crew’s success.

Flight Safety Foundation has defined a CFIT accident as, “one in which an otherwise serviceable aircraft, under the control of the flight crew, is flown unintentionally into terrain, obstacles or water, usually with no prior awareness on the part of the crew of the impending collision.”

In short, CFIT is the result of the loss of near-ground position awareness, the airplane is controllable and the results are fatal.

Looking Ahead

Anticipation

Pilots prepare for each flight. We flight plan and consider any number of factors including weather, winds, fuel consumption, alternates, approaches, airport characteristics—our situation list. We brief in explicit terms, developing expectations of what lies ahead.

In flight we alter our expectations to actual events. As we prepare for and adapt to change, it is desirable to have structured thinking processes to call on:

Maintaining Control

Making corrections

We want to keep control of our activities and decisions as smoothly as we control our aircraft. The familiar feedback loop is at work—input, output, feedback, correction. It’s exactly what you do or your autopilot does for you. Your cockpit management input is what you want to achieve—your objective, goal or target. Your output is what you’re actually accomplishing, your result. The difference between what you want and what you get is the information feedback is necessary for you to act to get back on target. Clearly, the smaller the deviation the smoother the correction.

Be committed to your objective. If you waver in this commitment, then you’ve given up a measure of control. Your autopilot is tireless in its commitment to your input. You need to “stay the course” on your cockpit (task) management activities as well.

Set boundaries or tolerances with respect to your objective. These may be rules set by your organization or guideposts that you’ve established for yourself. How much variation are you willing to accept? For example, we know that unstable approaches lead to CFIT accidents. Define clearly and set in your own mind what a stable approach is. Perfect entries are not always possible, but know at what point you must be stable (within your predefined tolerances or boundaries) or break it off. Stay in charge—control your destiny.

Expert CFIT Perspectives

Introductions

Dan Gurney’s career in aviation covered many years in military and civil flying, including experimental and development testing for a major manufacturer. He has more recently focused on safety initiatives, driven by the conclusions from incident and accident investigation. Dan has contributed to several industry and Flight Safety Foundation programs.

Thomas P. Turner holds an ATP certificate with instructor, CFII and MEI ratings, has a Masters Degree in Aviation Safety, and was awarded the 2008 FAA Central Region CFI of the Year, Tom has been Lead Instructor for FlightSafety International’s Bonanza pilot training program, production test pilot for engine modifications at Beechcraft, aviation insurance underwriter, corporate pilot and safety expert, Captain in the United States Air Force and contract course developer for Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University.

Tom now manages education and technical services for a 10,000-member pilots’ organization. Readers are encouraged to visit Mastery Flight Training, view its contents and signup for future issues of FLYING LESSONS Weekly.

CFIT Themes

Crew Behavior Patterns

[Dan Gurney] From my experiences of investigating CFIT accidents I have seen the following common themes involving situation awareness and crew monitoring.

Dan’s observations need to be clearly understood and CFIT prevention strategies should be sure to derive appropriate counter measures. It’s advisable to keep in mind that many CFIT accidents occur near airports into relatively flat ground, not necessarily into rugged terrain.

CFIT, a General Aviation Perspective

CFIT is GA’s second leading accident cause, the first being loss of control in-flight.

[Thomas P. Turner] CFIT occurs primarily in four varieties:

To avoid this second most common cause of fatal GA events:

Tom challenges all pilots, including Tom himself, to:

CFIT Video

Awareness And Prevention

A dated but useful video presentation, CFIT: Awareness and Prevention, has been restored in two parts and can be found on YouTube:

CFIT: Awareness and Prevention, Part 1

CFIT: Awareness and Prevention, Part 2

Viewing the video you will see the effects of scud running (by two very experienced pilots), an accident due to black hole illusion on a straight-in approach, and the result of confusing ATC clearances with communications conducted by parties who had different primary languages.

A concluding message: Acknowledge vulnerability and be vigilant.

By asking questions of ourselves we improve and maintain knowledge of the flight’s circumstances. For example, asking “What If?” helps prepare pilots for the choices they may face. In a similar manner, asking “What’s Next?” helps pilots prepare for the next upcoming task, the critical first step in setting that course of action.”

In-Flight Task Management

Just as “What If?” scenarios improve the pilot’s quality of judgment, asking “What’s Next?” helps the pilot maintain control of in-flight decision processes, doing the tasks required to achieve results. By asking “What’s Next?” a pilot keeps defining and redefining the tasks ahead in very specific terms.

Step-by-Step

Soon after starting a procedural step the pilot asks “what’s next?” to prepare for the actions that will be immediately required by the next step in the procedural sequence.

How many altitude busts, missed step-downs, improper procedure turns might have been avoided if the question “What’s Next?” were routinely answered?

Reducing Automation Reliance

This type of questioning might also aid in reducing automation reliance. When fully coupled, pilot-leaders engage themselves in the process. By seeing a task properly executed and then anticipating what’s next in very specific terms, the pilot will remain mentally involved and able to act should a demanding situation arise. Easily said, but in reality it takes concentrated effort to maintain this personal level of involvement.

Flight Preparation

When preparing for flight, professional pilots consider any number of relevant factors including weather, winds, fuel consumption, alternates, approaches, airport characteristics. In doing so they anticipate what may lie ahead and conduct pre-flight briefings in accordance with these expectations. The briefings are in specific terms, and the process well-ordered and thorough.

Flight Management

In flight, pilots adjust expectations to conform to actual events and potential risks. This process is also considerate, thorough and ongoing.

Advancing Flight Strategies with “What If” Scenario Building

“What If?” is a disciplined means of “game planning,” ideally suited for flight briefings and for developing in-flight strategies to evaluate potential alternative courses of action and then select a suitable action plan. It is a relatively simple step-by-step process whereby the pilot:

These steps are conducted for any situation that may be anticipated or is developing during the flight.

The “What If…?—Then…” logic is clear and direct. By following this method of reasoning, the pilot is able to put certain issues in perspective, gain greater awareness of the circumstances facing the flight, and be better prepared to exercise sound judgment by making quality choices and taking appropriate actions.

Cockpit Management.

The effective utilization of resources and the control of activities to safely accomplish the flight’s objectives.

Pilots are called on to plan, decide, communicate, execute strategies, conserve resources, interact, and perform numerous other flight related duties.

An Airmanship Essential.

The cockpit-leader commands the aircraft and exercises control over all flight activities. The essence of cockpit management control is to set sights, stay the course and achieve desired outcomes.

Management Control Depiction

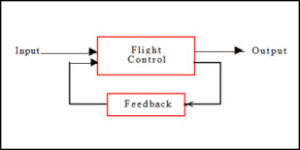

The Flight Control System

This concept of management control is analogous to the operation of a typical airplane’s flight control system. The basic function of such a system is the feedback loop. Referring to the accompanying figure, output (“where I am”) is compared with input (“where I want to be”). The dissimilarities are simultaneously fed back to the input side, and corrections are ordered by the system that is designed to alter the output to match the input. Timing and response must suit the situation, since inappropriate actions can worsen the outcome.

FCS

The pilot exercises management control in much the same way. Goals are set, progress information is sought and obtained, deviations are noted, and actions to meet defined goals are taken as required.

Boundaries.

Pilots establish and respect acceptable boundaries for their own performance, just as they respect the boundaries that frame aerodynamic behavior.

Phrases such as “backside of the curve” and “pushing the envelope” are often used in non-aviation settings. To those who fly, these phrases have real meaning, strikingly reinforced by occasional missteps. Intimate knowledge of boundaries, human and physical, set pilots apart from those who deal more theoretically with management concepts.

Stability and Control.

Control systems respond well when deviations and corrections are small, but control issues arise when the required responses are out of phase and/or relatively large in nature. These unstable conditions arise when the aircraft is operated near its performance limits, “pushing the envelope,” or the feedback quality is degraded.

When an airplane is hand-flown, the pilot becomes the flight control system. In certain flight regimes the pilot, through inadvertent control action, also can induce undesirable motions, most notably pilot induced oscillations.

Summarizing:

Management Control and the Leadership Diamond©

The Leadership Image.

Visualizing Management Control:

Management Control

Vision: Setting clear objectives

Courage: Taking effective corrective action

Reality: Obtaining accurate feedback

Ethics: Respecting boundaries

The flight control system analogy is chosen for its familiarity and understanding by the pilot community. The diamond is completely consistent with the FCS depiction and provides the pilot with a mental image of management control and its attendant strategic forces.